A sideways look at economics

A former colleague of mine once told me how, as a junior economist, he used to record economic data releases in pencil. Pencil, he told me, was the key so that data could be erased to make way for subsequent revisions! Nowadays, Fathom’s economists can simply click refresh on their Datastream Excel add-in; economic research has come a long way…

Last week we argued that economists currently have little to fear from artificial intelligence (AI). We argued that economists add value, not just in terms of intuition and creativity, but also in terms of personal interaction. In any case, we expect human economists to retain a comparative advantage over their robotic rivals for quite some time. But even now other forms of technology are having a positive impact on the economics profession.

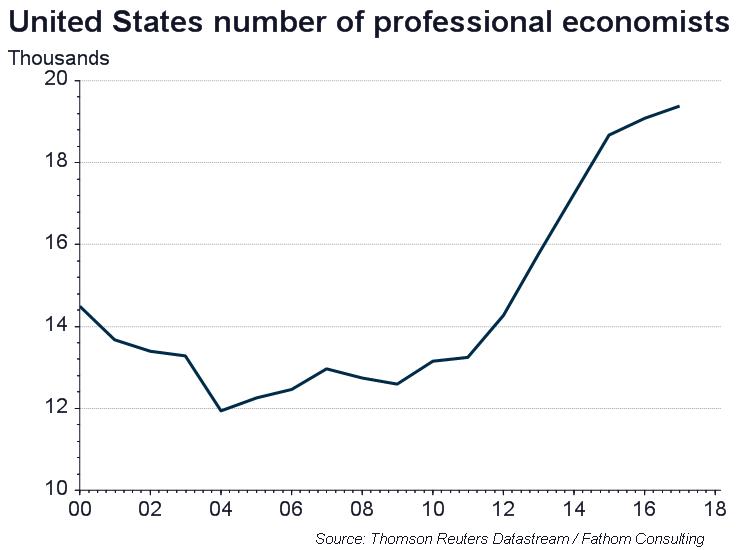

The example in the opening paragraph is one way. In days gone by, even the most basic data analysis was a time-consuming task. Half a century ago economists would calculate growth rates by hand and spend days running simple linear regressions. Today, the traditional role of the research assistant is fast disappearing. But such roles are not gone completely. The modern research assistant is a ‘jack of all trades’ and spends their day analysing data, running regressions and even writing research. Technological change has enabled young economists to shift from routine to non-routine roles, just as has happened in other industries. Indeed, economists are far from a dying breed – following the financial crisis interested parties flocked to us; some to hear our thoughts, others to berate us for letting the world fall apart…

And there are other ways in which technology has benefited the profession. Fathom, for instance, would argue that computerisation has even changed the economic data we should consume. Consider, for example, the business survey. For years, these questionnaires have been used as a leading indicator for hard data such as unemployment and inflation. But now, for the first time, these surveys have a serious competitor – Big Data. The average 21st-century individual leaves a significant digital footprint everywhere they go. That such data could dramatically improve the accuracy of economic forecasts is beyond doubt; the real question is whether economists can harness its full potential.

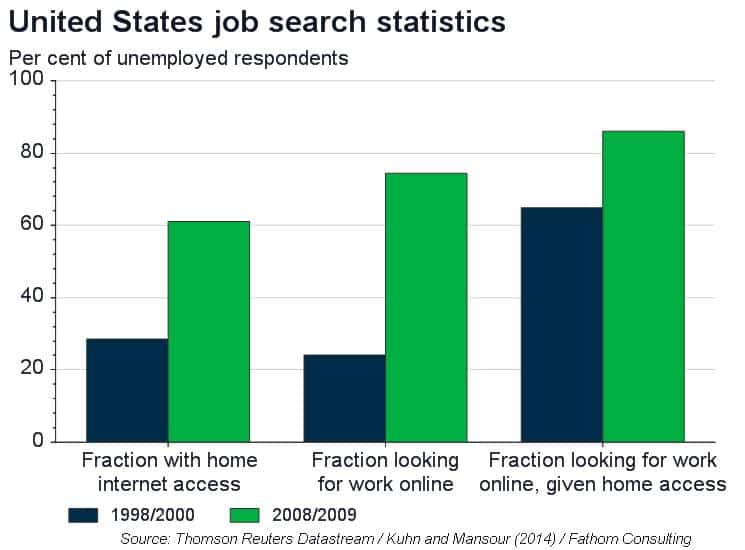

Consider the case of an unemployed person looking for work. Thirty years ago, such an individual would be found wandering the streets with a bag full of paper C.V.s. Now, the majority of people search for work online [1]. Surely then, Big Data can tell us something about unemployment.

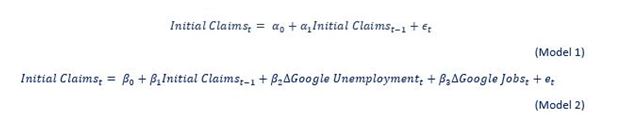

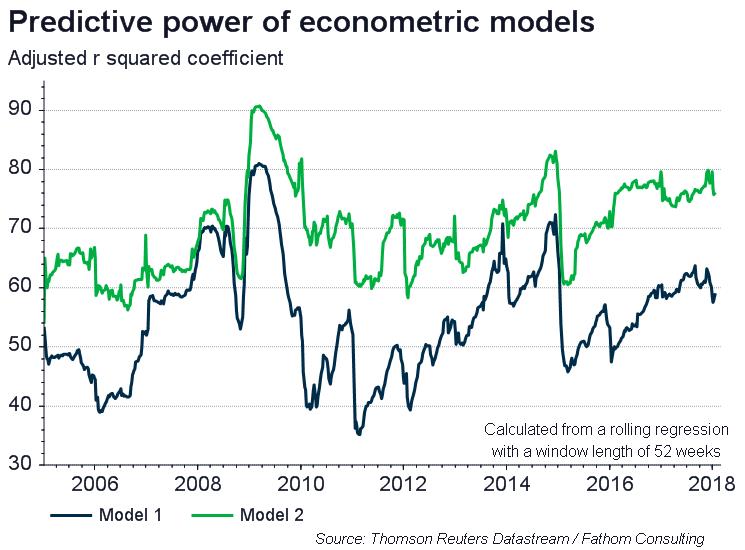

The Google Trends tool provides data on the evolution of internet search queries for specified topics since 2004. As other economists have shown [2], this data can be used to help forecast weekly initial jobless claims in the US. To see how this could be done, we have constructed two basic models. In the first, initial jobless claims is forecast simply as an autoregressive process. In the second, the changes in the Google query indices for both unemployment and jobs are added.

The results indicate that the second model performs slightly better. Arguably, however, this doesn’t really tell the full tale. Let’s recall that Google was still a relatively new invention back in 2004 and individuals’ search trends have changed considerably since then (as the chart above demonstrated). The two models have therefore been rerun on a rolling basis to account for the aforementioned changes in search trends. The chart below shows that the second model generally has a better fit than the first, suggesting that Big Data improves the model. Indeed, both models were used to forecast the initial claims data released on Thursday 25 January, with the second model reducing the forecast error by almost a third.

But the full potential for Google data doesn’t stop there. Researchers have sought to exploit this data source in order to forecast a wide range of economic variables including retail sales, house purchases and the demand for cars. Scientists have even used it to forecast the spread of flu!

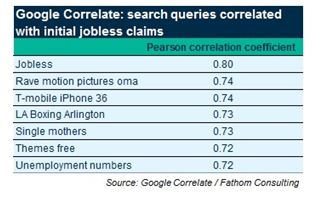

Of course, the question remains – can AI do a better job? Last week we argued that machines might one day gain an absolute advantage over economists. Google offers yet another Big Data tool (Google Correlate), which provides another insight into this. Whereas their Trends tool allows users to pick specified search queries, Google Correlate allows you to upload a series in order for it to pick the search terms most highly correlated with it. The table below shows the search terms most closely related to ‘initial jobless claims’. Some of these are plausible candidates for variables; others, ‘iPhone’ for instance clearly are not. Economists know the difference between causation and correlation; it appears that Google Correlate doesn’t, at least for now.

So, what does this all tell us? Clearly technology has already changed the way economists do their jobs and, as a profession, we must seek to embrace this change in order to improve our work. As highlighted above, Big Data gives us access to a host of new information and could enable us to create new indicators of economic performance. This is something that we’re actively exploring here at Fathom. True, it will be challenging but we like a good challenge.

[1] Peter Kuhn and Hani Mansour. ‘Is Internet Job Search Still Ineffective?’, The Economic Journal, 125/581,2014

[2] Choi Hyunyoung and Hal Varian, ‘Predicting the Present with Google Trends’, Economic Record, vol. 88, 2012