A sideways look at economics

Elevating my chair and peering around Fathom HQ, I am greeted by a display of the latest audio headwear, far more extensive than the range available in my local John Lewis department store. Two thoughts spring to mind. First, I should have asked my colleagues’ advice prior to buying my new noise-cancelling headphones. (Toby’s must be good, or perhaps it’s the guttural screams and blast beats of the black metal he chooses to listen to that divert his attention away from office chatter.) Second, it’s not only me that struggles to concentrate in our large, open office space.

But shutting out the office hustle and bustle is only part of the battle. It’s the internal chatter of a restless mind that gets to me. So, in addition to upgrading my ear-wear, this year I embarked on a journey of ‘mindfulness’. Once associated with tree-hugging and incense, this ancient practice of purposefully paying attention to the here and now is growing in popularity, working its way into both modern-day medicine and the workplace. Meditation and mindfulness give people the opportunity to take a step back from stress and pause for a moment before acting. Even my high-intensity sweatbox of a gym has made room for meditative classes,[1] and rightly so.

Estimates by the Global Wellness Institute (GWI), a non-profit organisation, suggest that the economic burden of mentally and physically unwell workers — in both medical expenses and lost productivity — is enormous, perhaps as much as 10–15% of global economic output. Spending as much time as we do at work (by my calculations, around a half of the day is spent working or doing work-related activities, which amounts to just shy of 5250 days in a lifetime), it is of little surprise that work is a major factor behind both happiness and stress.

Problematically, the latter is associated with an increased risk of poor physical and mental health, namely the development of chronic diseases, depression and anxiety. Conversely, a happy workplace can be a place for friendship, a source of joy and provide a sense of purpose.

As a consequence, most mid- to large-sized companies and multinationals now have some kind of programme in place to promote wellbeing among employees, with the likes of Johnson & Johnson and Boeing some of the first pioneers. Although onsite massages and lunch-time yoga sessions would be a welcome luxury (hint, hint), programmes vary considerably. Some remain fairly basic, with cover ranging from subsidised or free gym membership to counselling and lifestyle management interventions.

Workplace wellness is now estimated to be a £30-billion industry, with third-party providers of diagnostic tests, counselling services, and much more all cashing in. Even so, the GWI estimates that only 10% of the global workforce has access to workplace wellbeing programmes and services, with even fewer enjoying sufficient support. (The vast majority of programmes still focus on physical rather than mental health, and those that encompass the latter tend to provide only a ‘band-aid solution’, addressing the consequence and not the root of the problem within the workplace.)

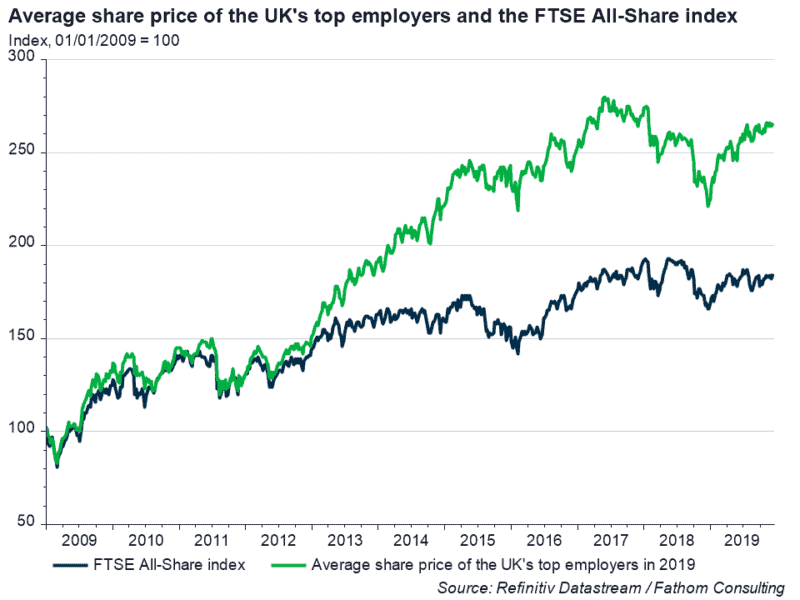

That is despite both survey and scientific evidence pointing to the benefits of comprehensive wellbeing programmes. According to one survey, around 60% of US companies believe their schemes reduce health care costs, with around 80% suggesting they reduce absenteeism and increase productivity. If that isn’t compelling enough, the business case is made all the more persuasive by research that suggests share prices of socially-responsible companies that invest in the health and wellbeing of their employees tend to outperform that of other listed firms. In other words, investing company resources in wellbeing programmes as opposed to the more traditional types of investment doesn’t appear have a negative influence on the company’s stock performance. In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

The chart below compares the average share price of the UK’s top employers in 2019, as judged by the Top Employers Institute and based on good HR practice, relative to the FTSE All-Share index. This shows that the selection of award winners for which we could find data (34 in total) have enjoyed share price outperformance for much of the last ten years, with the share price appreciating by 170% compared with the market average of 90% over that period.

Of course, there’s a question of causation, with more successful companies also better able to look after their staff, offering these programmes because they can afford to do so. In other words, it’s their profitability, as opposed to their exceptional treatment of staff, that’s being rewarded.[2] But to the extent that a company (and therefore its success) is precisely the people in it, the link between employees’ wellbeing and financial outcomes can’t be dismissed (think reduced absenteeism, enhanced productivity and greater engagement).

One way or another, investors are valuing firms that put their staff first.

Notably, the benefits extend beyond the company itself, with individuals enjoying reduced stress, anxiety and pain through meditation and greater mindfulness. Indeed, brain scans reveal that just ten minutes a day for eight weeks can help to train the brain to achieve sustained focus even when negative or stressful thoughts or situations arise, whilst simultaneously increasing both short-term memory and memory recall.

This January, just over half of us will resolve to better ourselves in some way, with New Year’s resolutions probably focused on shrinking waistlines and eradicating bad habits. But in addition to the usual half-hearted goals of drinking less alcohol and exercising more, I’ll be focusing on a healthy mind. There may be little we can do to fend off the common cold at this time of year, but at least we can combat the winter blues.

[1] My first (and last) foray into a class known as Brain-gasm did not have a happy ending. Instead, the supposedly dulcet tones of the instructor were drowned out by loud grunting and groaning from the weights room downstairs.

[2] Those concerned with employee wellbeing may also possess other favourable qualities, such as environmentally friendly practices and staff diversity, which influence their market valuation.