A sideways look at economics

Within a month of its launch, Squid Game, a South Korean dystopian thriller, became the top-performing Netflix series to date. The show graphically explores the lengths to which desperate and debt-ridden people will go to escape the clutches of crippling personal debt. With ‘players’ invited to take part in a series of deadly children’s games, facing off against one another to become the sole winner of ₩45.6 billion (£28.9 million/$38.7 million) — a life-changing prize and experience for the last-man-standing.

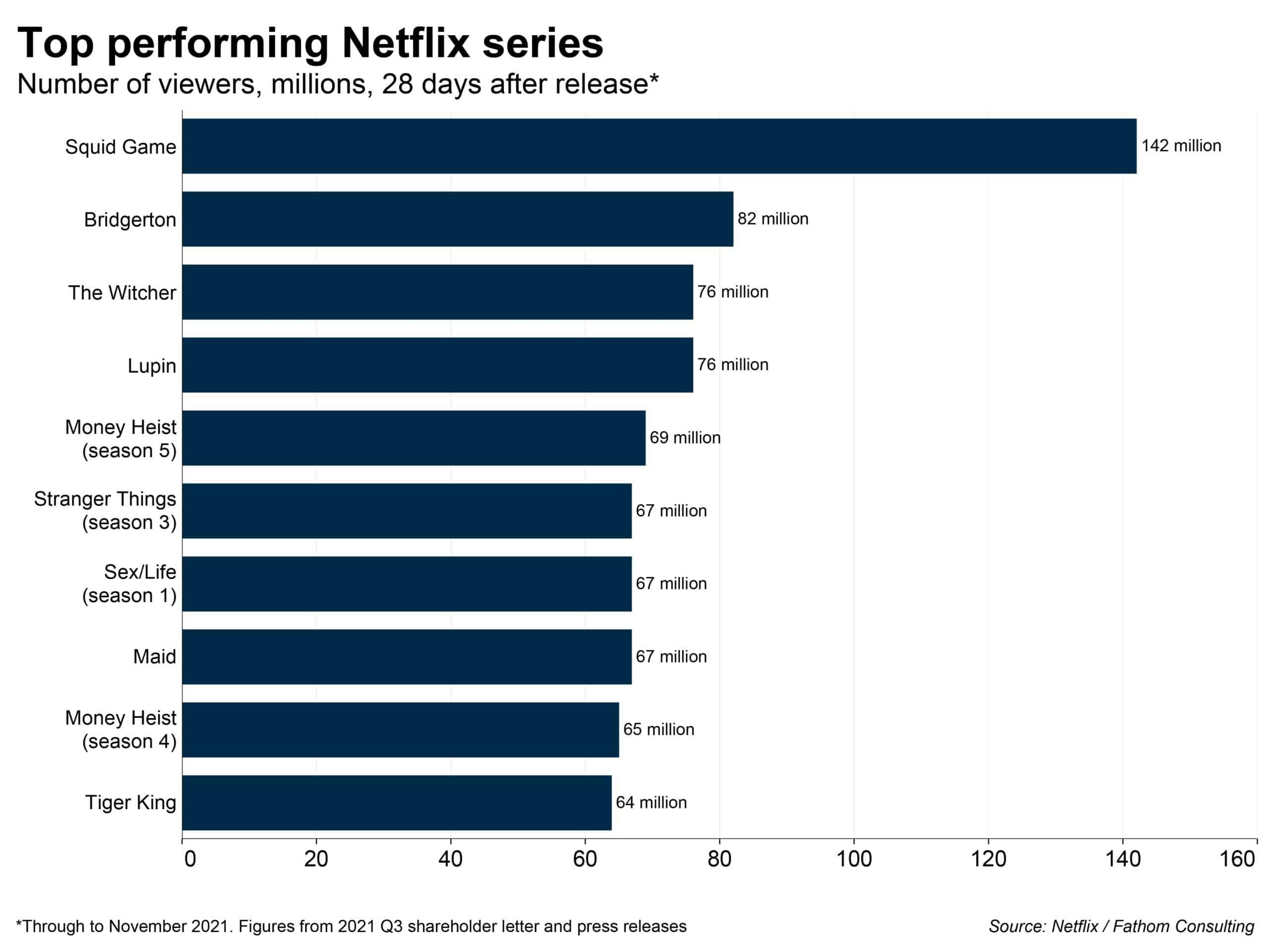

With 142 million of us tuning in during the first month of Squid Game’s release, there’s no doubt that part of the viewers’ fascination with the show is due to the allure of the violent scenes and glamour of survival games that its predecessors (such as Battle Royale, The Hunger Games, and Maze Runner) have popularised. The show, however, also resonated profoundly with me for a more sobering reason…

That is, that the show is an allegory on economic inequality in today’s developed world.

Hwang Dong-hyuk, the show’s writer, describes Squid Game as a “fable about modern capitalist society”, as “something that depicts an extreme competition, somewhat like the extreme competition of life”.[1] For many of us the themes portrayed in the show confront the day-to-day issues we ourselves, or others in our communities, struggle with, be it high household debt, inequality of opportunity, the inability to pay for healthcare and utility bills, or being unable to keep up with the cost of living. The show confronts the inconvenient reality that many modern capitalist societies leave some people feeling economically left behind.[2]

As the plot of the show develops viewers are introduced to various characters, each with their story to tell. Hwang Dong-hyuk expertly crafts his characters in a social commentary on some of the pervasive problems South Korean society faces today.

First, we have the protagonist of the show, Seong Gi-hun. A divorced father and gambling addict with a mountain of debt he has no hope of ever clearing. He struggles to financially support his daughter and enters the ‘squid game’ in a desperate attempt to settle his many debts and prove himself financially stable enough to share custody of his daughter.

Seong Gi-hun’s character illustrates South Korea’s long-standing problem with personal debt. Household debt stands at 201% of national disposable income in 2020, the fifth highest in the OECD on this measure, and in excess of 100% of GDP, which is among the highest in the world. Indebtedness is flagged as a major potential risk by the Korean Financial Services Commission.[3]

Seong Gi-hun, unable to afford a place of his own,[4] lives with his elderly mother Oh Mal-soon. Although old, she works selflessly to support them both by working long days selling goods at a market stall. She suffers tremendously from a chronic condition which she cannot afford to treat — leaving her stall even for a day will cost her too much in foregone income — and so she refuses to seek treatment for her ailments at her local hospital.

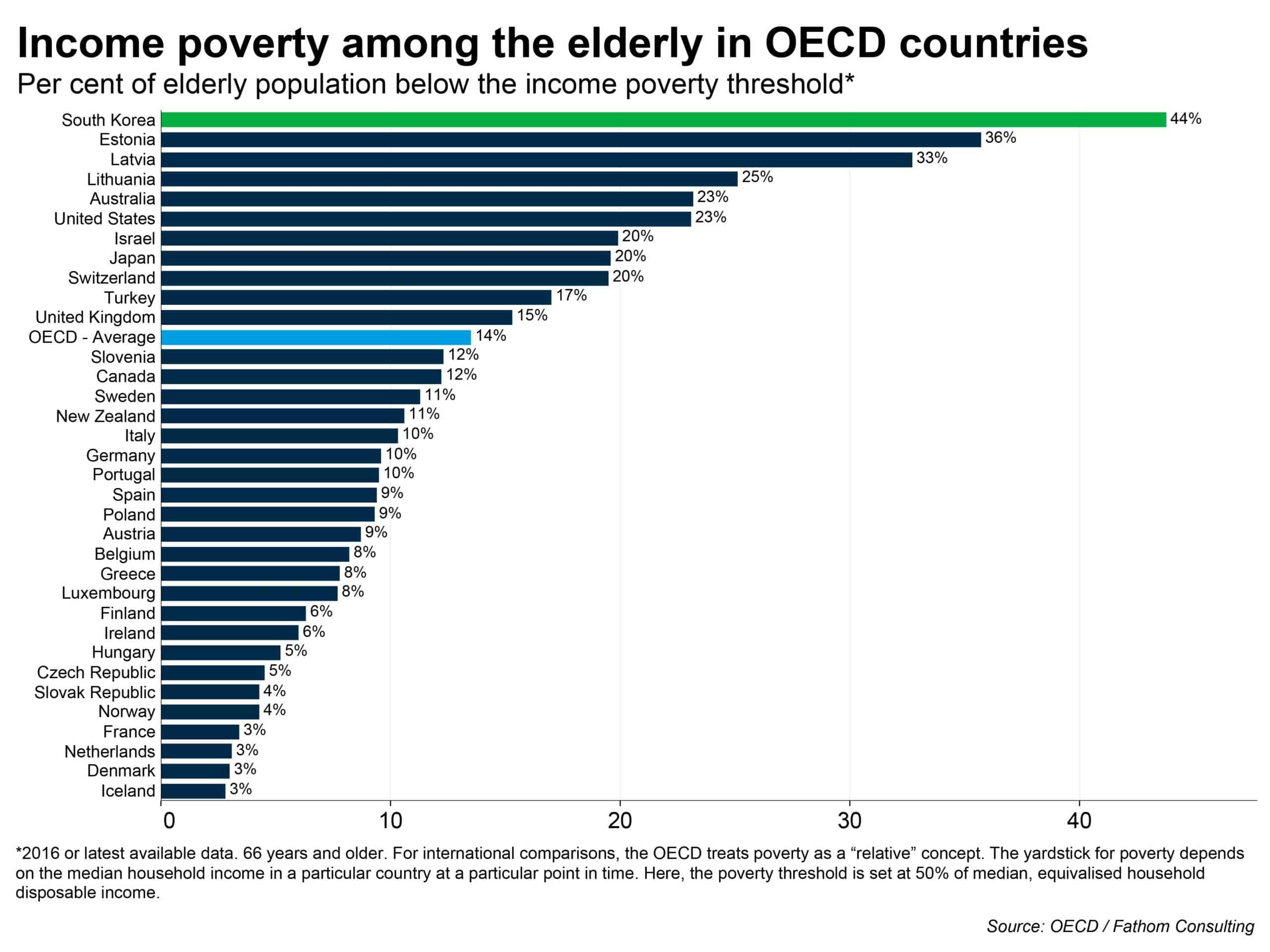

Oh Mal-soon and the other elderly ladies working the market stalls reflect South Korea’s difficulties tackling poverty among the old. Many elderly South Koreans are unable to afford to retire, and spend many extra years in the workforce, often in highly insecure, informal, and low-paying jobs.[5] South Korea’s elderly poverty rate is by far the highest among all OECD countries — with over 44% of those over 66 falling below the poverty threshold (compared to 14% for the OECD on average).

Early on in the game Seong Gi-hun is joined by Abdul Ali, an immigrant from Pakistan. Ali is a selfless and kind-hearted character, who arrived in South Korea with his wife and child hoping to give them a better life. As an informal worker he enters the game not because he is struggling with debt, but instead because the nature of his work means his boss does not pay him for many months at a time. He hopes to earn enough money through the game to support his family.

Ali’s troubles represent those faced by many immigrants when seeking economic security and a better standard of living abroad. Jobs can be hard to come by and many immigrants find themselves in low-paid, temporary, or informal work. Ali is both bright and hardworking, yet despite his attributes, his hand is forced, and he chooses to enter the game in an attempt to break the cycle of labour exploitation, discrimination and poverty.

Finally,[6] Kang Sae-byeok, a North Korean defector, places each contestant’s plight in context. Having already risked her life to escape North Korea,[7] we discover in an emotional moment in episode 6 that she entered the game to help earn enough money to help reunite her family. A disastrous border crossing left her father dead, her mother in captivity, and her brother in an orphanage.

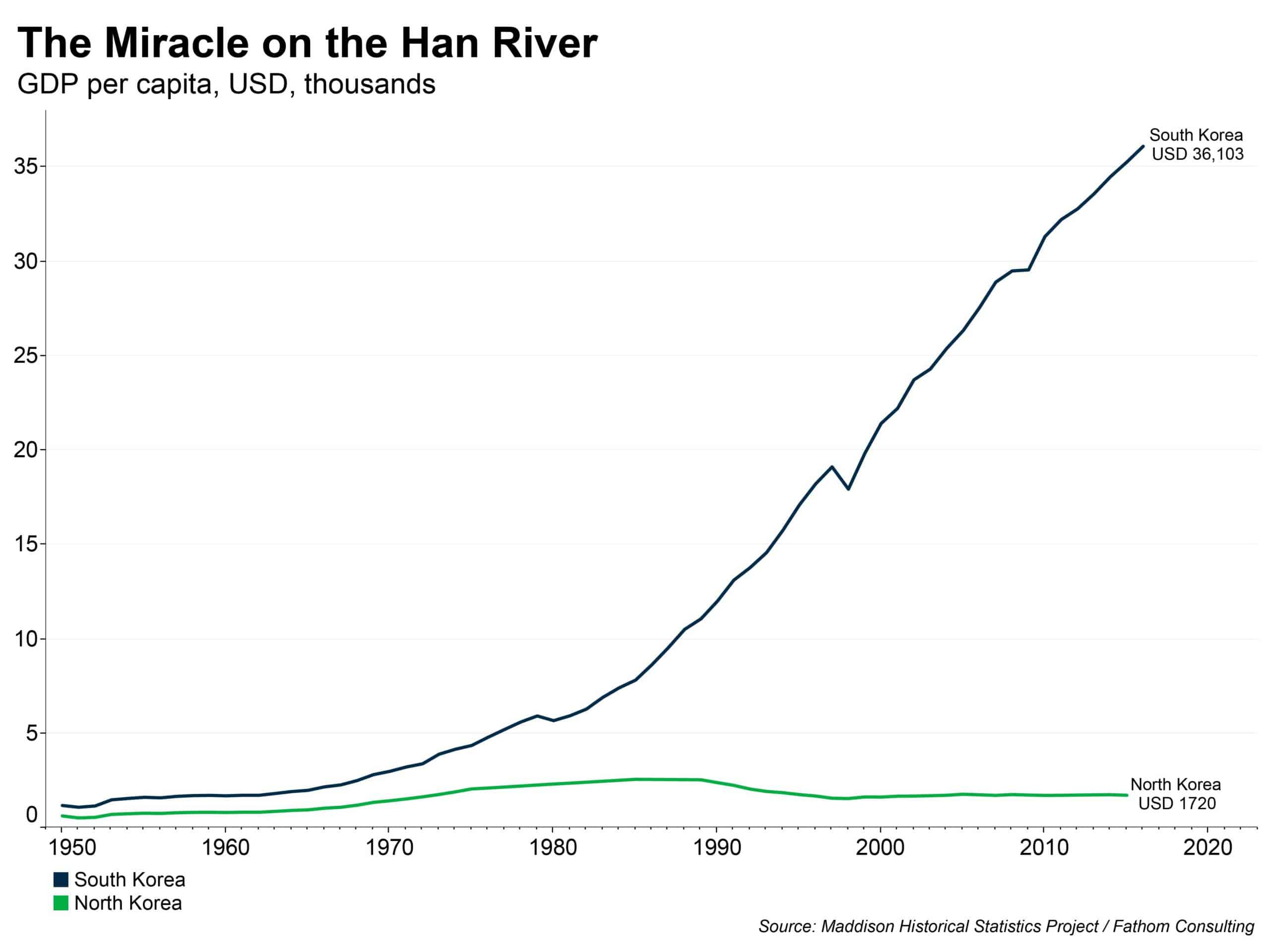

Kang Sae-byeok’s story illustrates the difficulty defectors have integrating into South Korean society, and reminds us of the economic conditions her compatriots face on the other side of the DMZ. South Korea’s post-war boom (coined ‘The Miracle on the Han River’) saw GDP per capita in South Korea rise from $1478 a year in 1953 to around $36,000 nowadays. By contrast, it is estimated that the average income in North Korea only increased by around $700 in the past half century — approximated at a mere $1720 in 2016.

Throughout the game we discover the lengths hopeless people in desperate situations will go to. The moral dilemmas they face leave viewers questioning how they would react in each challenging situation.

I for one, enjoyed Squid Game for what it is — an exciting, thrilling, and often gory display that grows ever more captivating as the players become increasingly desperate to win the prize money.[8] But if you are anything like me and also partial to taking a moment to think more deeply about the show’s message, I hope that when you watch (or watched) the show, that you can reflect and be grateful for the many good things our modern societies allow us to have, while also reserving a little empathy for those around us on the fringes of society that don’t share in the same good fortune. If the show taught me anything, it’s that it’s important to remember there are always stories behind the statistics.

[1] https://variety.com/2021/global/asia/squid-game-director-hwang-dong-hyuk-korean-series-global-success-1235073355/

[2] A particularly poignant point in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as the poorest households are likely to be hit hardest by the pandemic’s economic fallout. https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n376

[3] https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2021/09/28/business/finance/household-debt-FSC-increase/20210928172701939.html

[4] Numbeo estimates property prices in Seoul to be 30x average income (vs 14x in London): https://www.numbeo.com/property-investment/in/Seoul

[5] https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/korea-should-improve-the-quality-of-employment-for-older-workers.htm

[6] “Finally” only in the sense of wrapping up this short blog! There are many more characters portrayed in the show — each with their own reasons for entering the game. I’d recommend tuning in and discovering their fortunes if you haven’t binge-watched the series already.

[7] Kang Sae-byeok attempts to hide her North Korean accent as she seeks to avoid discrimination from the other South Korean contestants. This is something that cannot be truly picked up on by non-Korean speakers. Digital Spy explains this (although, be warned, this article contains spoilers!): https://www.digitalspy.com/tv/a37849780/squid-game-hoyeon-jung-kang-sae-byeok/

[8] This is a great example of sunk cost fallacy!