A sideways look at economics

I’m on the brink of a move to the US, prompting some reflections amidst the packing. I’ve made a number of moves before — the first as a child from the North of England to Ireland, the place I now firmly call home. Relocations can be motivated by lifestyle preferences, career objectives, family life and, very sadly for some, by the search for safety from conflict or persecution. Moving satisfies those needs, but there is also something lost in the process: we can lose our sense of belonging, of being of somewhere. Other lives are also affected when we decide to leave our community – negative externalities, if you like. Economies benefit from labour mobility in the short-term and there are undoubtedly huge benefits to the skills and diversity brought by migration – but is there a long-term cost to more transient societies?

A few Prime Ministers back, there was one called David Cameron. (We don’t hear much from him these days, his premiership umbilically linked to one decision.) When this sprightly young Tory came to power in 2010, a cornerstone of his party’s manifesto was the ‘Big Society’. This election slogan was a promise to redistribute power to communities and to promote volunteering and kinship.

In essence, the Big Society was an attempt to correct market failure: we need vibrant communities, but economic growth is not always consistent with their preservation. The assumptions that policymakers make about how our economy operates are, necessarily, too simplistic to capture the impact of personal relationships; and hence our strategies to expand the economy largely ignore their role.

Micro-economic theory assumes economic actors to be self-interested. They are individuals who make decisions to maximise their own interests. To reference an-oft quoted Adam Smith line, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” It is this self-interest, guiding Smith’s ‘invisible hand of the market’, that underpins neoliberal economic policy. But it is hard to square that understanding of human behaviour with the many unrewarded acts we see in day-to-day life.

At a macro level, economists see economic activity as the combination of our productivity and our factors of production, like capital and labour. The Cobb-Douglas production function[1] is a way of transforming these inputs into an estimate of the productive capacity of the economy. That process tends to limit estimations of capital to its physical forms, like structures and equipment, while incorporating the impact of educational attainment and technology through the total factor productivity coefficient.

Community can be thought of as social capital, a largely ignored factor of production. The OECD (2001) defined social capital as the “networks together with shared norms, values and understandings that facilitate co-operation within or among groups”. Research supports the idea that social capital matters: those communities with deep social networks have been found to be better at confronting poverty (Moser, 1996) and to adapt more quickly to new technology (Isham, 1999). From purely a growth perspective, Putnam (1993) was the first to establish a link between civic engagement and differences in regional economic performance in Italy. Subsequently, Beugelsdijk and Van Schaik (2005) found that social capital also explains economic growth differentials across European regions.

There is good reason why social capital is largely ignored: it’s nigh on impossible to measure. And while it is relatively easy to design policy which deepen our reserves of physical capital, building social capital is more complex.

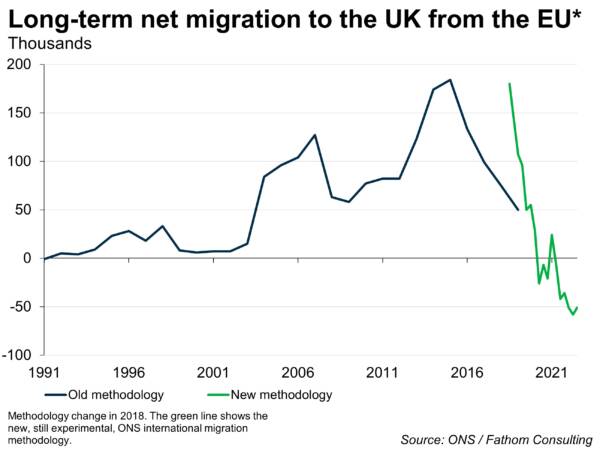

Of course, a vibrant community comes from more than just folk staying put; communities are greatly enhanced by those arriving to take new jobs and create new connections. The sharing of new ideas from new places enriches others. A stable community can become a sterile environment, prompting outcomes like nepotism and cronyism that weaken governance and productivity. And labour mobility helps to fill regional skill shortages and raise productivity. At this point I’m reminded of Mr Cameron and the current shortage of workers in certain sectors, now that moving to and from the UK has become much more difficult. Despite Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey claiming otherwise this week, it seems clear to many that these labour shortages are partly owing to the immigration restrictions of Brexit.

Community matters, relationships matter. Some are strengthened by fluidity, others possibly weakened. It is impossible to capture the nature of community in economic models but we need to remember its importance when designing and growing our economies.

“Like feathers on the ocean breeze

They went spinning and tumbling ‘cross the sea

Never know where they’d come down

Or who they’d be”

Passenger, ‘To Be Free’

[1] In the Cobb-Douglas framework, output is represented by a combination of factor inputs, and their elasticity to output (a), multiplied by the level of technology in the economy or TFP (A).

More by this author

Premier League vs productivity