A sideways look at economics

I recently attended my best friend’s wedding in County Sligo and, in an effort to elevate my otherwise fairly low-brow speech, included a line from WB Yeats, who adored that part of the world. Given that Yeats’ poetry is predominantly about the frustrations of unrequited love and patriotism, I had to hunt through his work to find the line that would raise glasses rather than handkerchiefs! During that search, I reread ‘September 1913’, a timeless masterpiece that still makes spines tingle over a century later. The poem sees Yeats describe a country which has come to prioritise materialism at the expense of feeling and idealism: which brings me to Christmas and the question of what this annual extravaganza means to increasingly secular Western societies. There will be Christmas goodwill here, folks, I promise. Just be patient.

Excerpt from ‘September 1913’ by WB Yeats

What need you, being come to sense,

But fumble in a greasy till

And add the halfpence to the pence

And prayer to shivering prayer, until

You have dried the marrow from the bone;

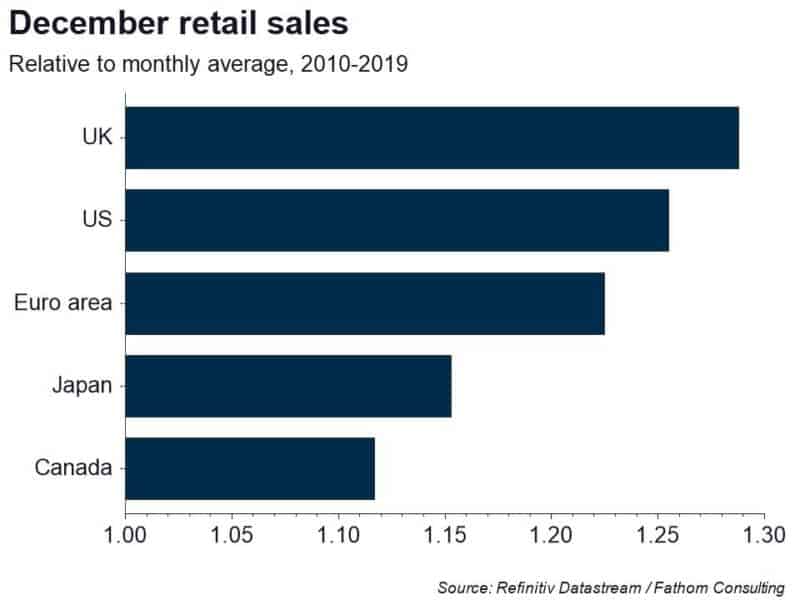

I’m not quite sure what Yeats would have made of the annual John Lewis Christmas advert. These seasonal marketing campaigns tug on our heart strings and trigger our desires, boosting corporate earnings in the process. No doubt, they are effective – according to the Bank of England, the average UK consumer spends an additional 29% in December compared to a typical month. The seasonal deviation in UK retail sales appears outsized by comparison with other advanced economies, as shown in the chart below. At least we know the game, though: according to a YouGov survey, almost a quarter of Brits think that Christmas wouldn’t be celebrated were it not for pressure from commercial entities. There’s no sign of that stat in your Christmas cracker.

Christmas plays such a critical role in global economic activity that Beaulieu and Miron concluded it is the key determinant of seasonal patterns around the world. Even those soulless financial markets seem to get into the spirit, with an apparent tendency for equities to overperform on the final trading day before Christmas.

This is all despite religious faith having plummeted. According to the recently published results of last year’s UK census, only 46% of the population now identifies as Christian. That’s 13 percentage points lower than a decade ago. On the other side of the ledger, there was a 12-percentage-point rise in those reporting themselves of “no religion”, who now represent one in three of us.[1]

Most of the seasonal gestures that we perform this month– advent calendars, carol-singing, the giving and receiving of gifts – have obvious religious significance, but this matters less and less to the population. What does this festival now represent, then, other than a boon for retailers, restaurateurs and publicans?

Well, firstly, it’s always been the time of year for a feast, particularly in Northern Europe. Long before the birth of Christianity, pagans celebrated winter solstice and the promise of brighter days to come. The term ‘yule’ derives from ‘jol’, the Scandinavian term name for those ancient festivities. In fact, many claim the Christmas tree is a remnant of that earlier celebration, where yule logs or trees were burned to celebrate the life-giving properties of the sun.

We also celebrate in December because we have time to do so – and crucially time to recover. Unlike on the continent, there is no tradition of the August shutdown in the UK, but the upcoming period sees the greatest concentration of public holidays in the annual calendar with three in seven days. Most offices run on a skeleton staff or close altogether, with Fathom no exception. We fill up our lungs, and celebrate the year that has passed and the new one to come.

Gift-giving is a symbol of the three wise men, but in the absence of that association for many of us, it is instead an excuse to offer family and friends something they need or, preferably, something they want. Some microeconomists see it in a less positive light. In a divisive American Economic Review paper, Waldfogel argued that the exercise is an inefficient way to allocate resources: by potentially leaving the recipient worse off than if he/she had made their own consumption choice, gift-giving is a source of deadweight loss. Evidently, thoughts don’t count in a utility function.

Last but not least, we may live in an increasingly secular society, but this Sunday represents a prominent, even inescapable, reminder to many of their faith. Over the Christmas period, attendance in the Church of England is more than double any other week of the year.

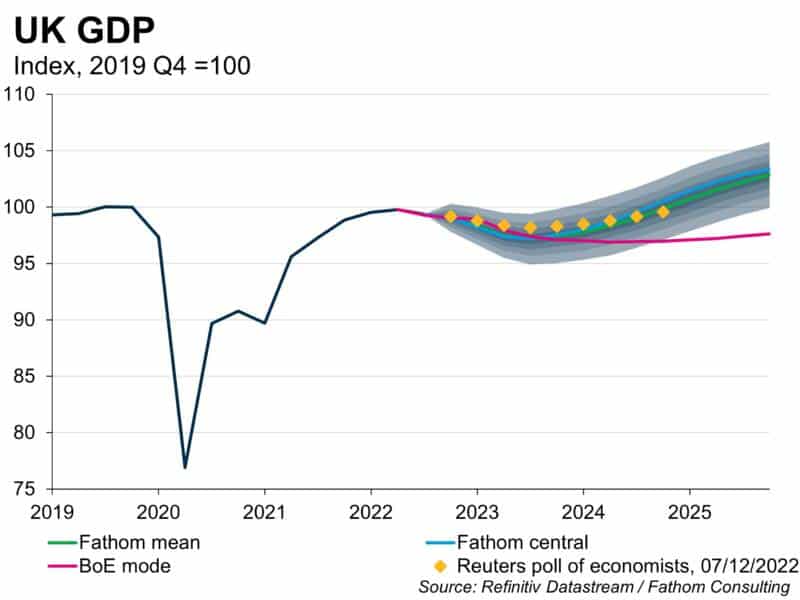

This year’s edition arrives amid generally challenging economic circumstances in the UK. On the positive side, a tight labour market has driven multi-decade highs in nominal wage growth, and enough pandemic savings remain for the odd bottle of bubbly. However, inflation-adjusted incomes have fallen sharply this year, borrowing costs are higher and consumer confidence is at a very low ebb, with the economy contracting in the third quarter. Festive spending is expected to be more muted as a result and, on a seasonally adjusted basis, Fathom expects the UK economy to contract again this quarter. Did I say there was going to be festive cheer?

For once, though, let’s put the economics to one side. I’ll be celebrating with my in-laws in Paris this year, and our cultures and beliefs vary, like in many families. Our seasonal traditions reflect our diversity, but there’s one thing I insist on: proper gravy with the bird, not just ‘un jus’. Merry Christmas and enjoy the party, for whatever reason you choose to celebrate.

[1] The next highest share of the population is Muslim (6.5%), followed by Hindu (1.7%). Although replies to the question were voluntary, 94% of the population replied

More by this author: