A sideways look at economics

Since it started in 1995 as a website which only sold books, Amazon has morphed into a $1 trillion, global e-commerce behemoth, or ‘an everything store’ realising the vision founder Jeff Bezos had for the company when he started it from his garage. Much like a number of the world’s biggest brands, including Apple and Microsoft, Amazon had humble origins. In those early days, the power required to run early vintages of what would eventually become the Amazon servers meant the Bezos family needed to be careful not to run the vacuum cleaner and hairdryer at the same time lest they risk blowing a fuse.

How times change.

Fast forward to life at Amazon beyond Bezos’s garage and into a regular office. In the very early days of Amazon’s trading life, when a sale was made, a bell would ring, alerting (the very few) employees at the time to the good news. I can confirm that we have a similar process here in Fathom Towers, but unfortunately, we don’t sell as many books! Maybe a possible area for expansion?! Given Amazon’s exponential growth and domination of the e-commerce market, are we likely to see any real economic fallout from such an abundance of goods available with a single click of a button?

How many times have you walked into a retail store on the high street, checked out the product you wanted, and then bought it from Amazon for less money? This phenomenon even has a name: ‘showrooming’. But where are all of these products stored?

Amazon’s vast, out-of-town warehouses laden with products are partly serviced by machines and robots with minimal human intervention. Old-fashioned bricks-and-mortar shops on the high street struggle to compete on price given their substantially higher fixed costs. Amazon exploits economies of scale, operating on razor-thin margins but with a high volume of transactions. In 2017, 44% of all e-commerce sales in the US took place on Amazon, translating into almost 4% of all US retail sales. The behaviour of companies like Amazon increases the pressure on bricks-and-mortar retailers, dragging down prices across the board.

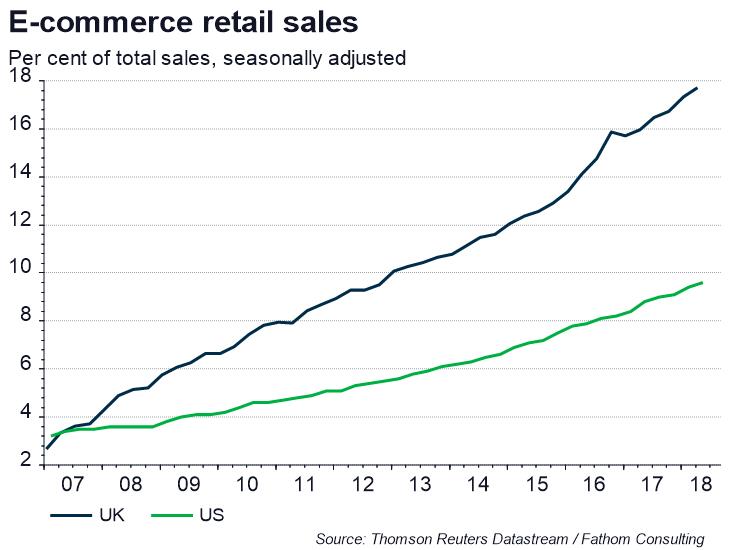

There is a general perception that inflation isn’t what it used to be. Despite near-zero interest rates, and massive injections of central bank liquidity, inflation has yet to take off around the developed world. Since the FOMC first began publishing forecasts for core PCE inflation more than five years ago, the targeted measure has repeatedly turned out to be weaker than expected. Is the rise of the internet part of the explanation? The above illustration suggests one way in which it might be. By encouraging customers to shop from the comfort of their homes, it has reduced the marginal costs of production in the retail sector, putting downward pressure on retail prices. But there’s another potential channel too.

By facilitating rapid price comparisons, easy access to the internet ought to raise the level of competition across all industries. Amazon’s prices can be checked 24 hours a day and compared with prices charged by their online competitors. But this is true of all e-commerce — not just business to consumer, but business to business. There is a difficulty here, though. If the rise of the internet has led to greater competition across the economy, we ought to see increased output at the expense of lower margins. But that sits oddly with rapid growth in corporate profits, particularly in the US, and stagnant productivity.

We also need to think about how inflation is measured. The traditional measure of using a basket of consumer goods to measure the general increases in prices isn’t well suited to the constant influx of new and upgraded products available online and it’s a difficult task to keep up with all the price and product changes. A few years ago, Adobe Systems created what it called the Digital Price Index and found that internet prices are rising at a much slower rate than you’d see in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). This was, in part, due to the different product groups used in the various indices while not forgetting that a number of the current constituents of the existing CPI basket are not purchased online. Producing a representative and timely metric for the general rate of price increases in an economy is vital for assessing its overall health, but given that e-commerce has, and continues to, disrupt the retail sector, we’re only just beginning to see the impact on the real economy. With the shift towards online retail set to continue, it may force policymakers to consider overhauling the construction of the index so that online sales are better represented.