A sideways look at economics

Last week, the whole of Fathom gathered in a lovely country mansion for our first ‘away day’ in three years. Serious conversations were had, as were significantly less serious ones; a sordid murder mystery was solved amid incessant innuendo and balderdash; pranks were carried out and Olympic efforts undertaken; and all was accompanied by good food and copious amounts of drink. Truth be told, a lot of the drinks cabinet stayed untouched: not an indication of restraint, I’m afraid, but rather of the over-optimistic purchasing of the otherwise flawless organisers. One of the memorable images I retain was of Laura, Fathom COO and visibly pregnant, driving home alone in a car literally overflowing with bottles. It would have made a great comedy sketch had she been pulled over and had to explain what was going on. It did not happen, which is great news since it means we can probably all look forward to another Fathom get-together to go through the surplus stash, maybe to celebrate the new Fathom offspring.

One morning at the retreat, in a sterling effort worthy of my former 20-year-old self, I dragged myself out of bed only to immediately crash again onto a massage table. I was not at my most functional — not until the outstanding breakfast lent me a miraculous new lease of life — but I felt strangely well. It was nice to be gathered together again in one place. Really nice. I try to make a point of remarking on occurrences that bring me joy. It is important to counterbalance an otherwise negative drift tendency, and also to take note, understand, generalise and reproduce these feelings elsewhere. It may be a professional habit that has seeped into my daily life, or perhaps it’s the other way around. Economics, as a social science, has a tendency to blur these lines and almost becomes a way of life.

In this instance, I could easily recognise where the good feeling was coming from: contact and social interactions. We are a social species. For some more than others, being social is also closely characterised by a physical and tangible dimension. I’m one of these people. I have always enjoyed hugging, jumping, tackling, shaking, tussling others and encourage others to do the same to me. I seek physical contact in a reciprocal way. A handshake, a tap on the shoulder, a high five, a laugh together or even just making eye contact are all small gestures – irrelevant, even obnoxious to some – that give me genuine pleasure and create strong bonds.

In my daily life the pinnacle of this primordial instinct appears in the evenings, in a small routine with my kids that has taken hold since they were just old enough to speak and that makes me extremely happy to this day. The Zazza household refers to this moment as: ‘imbraciato times’. It is a mix-and-match of English and an adulterated word from the Italian ‘abbracciato’ that my kids inadvertently coined as they were learning to speak. The verb ‘abbracciare’, or to hug, in Italian derives from the Latin ‘ad brachium’ which means to bring the forearm close [to someone]. I never corrected them to say the proper word as the ‘in’ prefix instead of ‘ad’ seemed more fitting of the greater intimacy and connection of our moment together.[1] The call to ‘imbraciato time’ refers to an exclusive bedtime moment between me and the kids where we closely hug each other in bed and chit-chat about our day: the funny bits and the drama in the playground, class, work; the challenges of the day and generally mindless, aimless, happy, free conversation. The talking can go on for some time as the incentives are aligned: they get to delay bedtime and I get to spend more time with them. After about half an hour of chit-chatting, I generally threaten to go. They somehow think it is a credible threat and negotiate for me to stay under the promise that they would be quiet and fall asleep. This moment is the culmination of bliss for me, I hold them tight and guide them into the arms of Morpheus while enjoying some quiet reflection time for myself. Not unusually, although less and less frequently as they grow up, I would also fall asleep along with them, often for the night. The three of us would invariably end up on top of each other and in a tangle of arms and legs, which no-one seems to mind and which does not prevent us from having a restful sleep. ‘Imbraciato time’ seemed particularly fitting way to describe to all this, and the name has stuck.

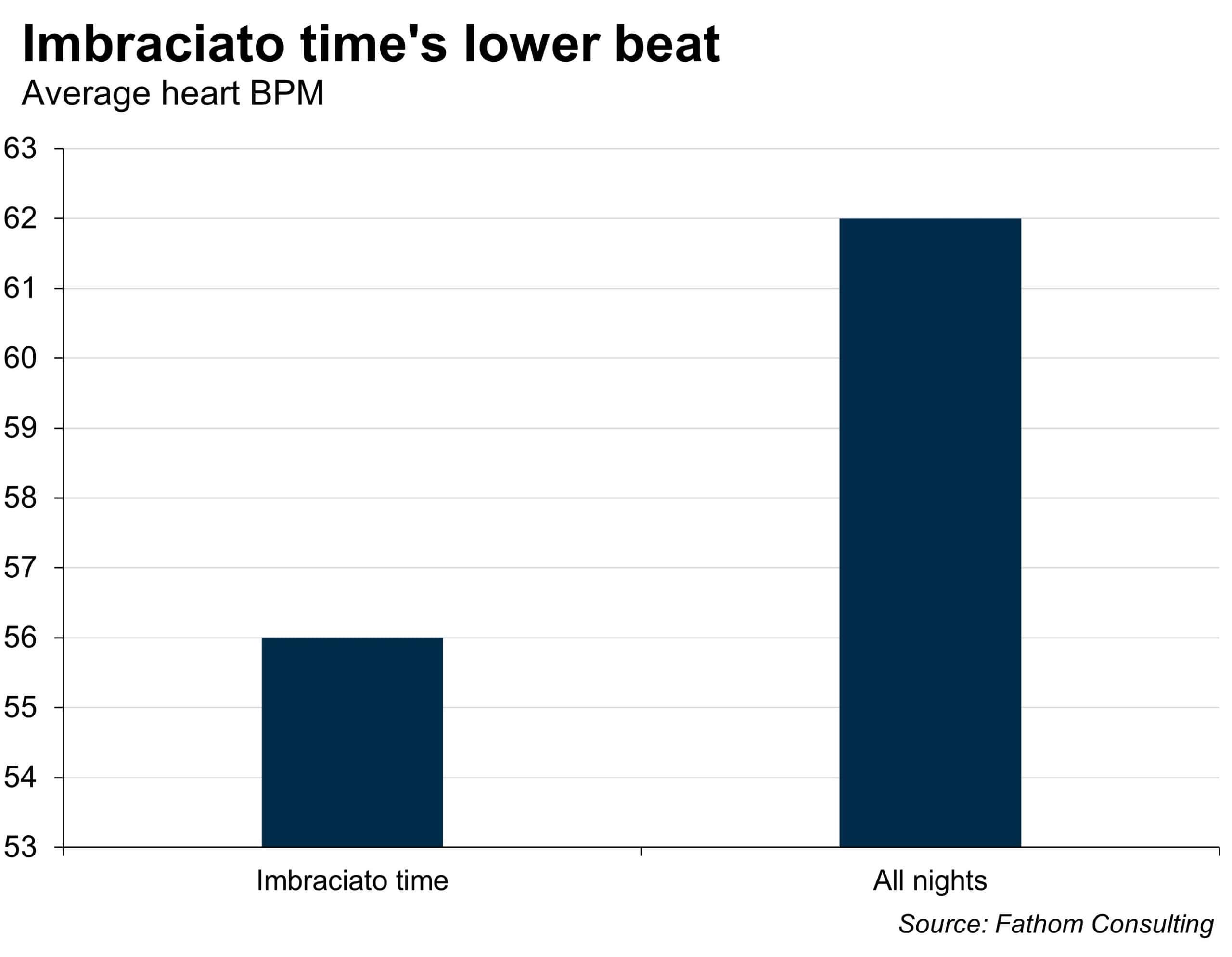

The reason for sharing this is that I have always wondered whether happiness has tangible benefits. Being happy is a great feeling, but is there more to it than just a chemical reaction? As one of the happy, easily repeatable moments in my life, by chance I happened to notice that the nights I fell asleep with the kids during ‘imbraciato time’ were also associated with a lower-than-average heartbeat and better sleep — at least, according to my fitness watch. I was intrigued and kept monitoring this hunch. The chart below reflects the average heartbeat of those nights where I capitulated to ‘imbraciato time’ versus the average across all other nights.

The difference is relatively striking, and I kept doing some digging. It turns out that there is also some academic research showing that hugging and touch has some clear health benefits, some of which are precisely the lowering of the heartbeat and better sleep (see here and here for a couple of examples).

If hugging and touch are associated with better health outcomes and make us happy, then perhaps this proposition can be generalised further. Would it not be great if anything that made us happy could also be good for our health? This is the thought that came to me lying down while having a massage at the ‘away day’. I felt smug about this idea, and happy, as I was genuinely enjoying my time with my colleagues, the surrounding, the activities, the debates and the massage. As this came to an end and I got up, the excesses of the night before came back in full clarity. Any pretence that happiness might be associated with better health quickly vanished — but the memories will certainly stay.

More by this author