A sideways look at economics

Early on 31 December 2020 the two biggest alliances in the known universe began the largest and bloodiest battle ever witnessed. The Imperium had managed to damage a key component of the PAPI Coalition’s military strategy: a Cyno Jammer, with the function of blocking warp gates, the technology through which entire fleets are able to jump into warzones. Without the use of its jammer, the PAPI Coalition was unable to control the flow of friendly and enemy starships and became vulnerable. The Imperium, a galaxy-spanning empire which ruled most of the known universe with an iron fist, had plenty of reinforcements to spare and rushed them to the front. And so began the Massacre of M2-XFE.

The battle saw the loss of thousands of virtual starships. With 7,000 player-controlled pilots pitting themselves against each other in online space warfare, the fighting sent shockwaves across New Eden, the name given to EVE Online’s universe. Of course, EVE Online isn’t a part of reality, but rather a massively-multiplayer, online virtual game in which 9.6 million players work and fight for resources. Created by CCP Games in 2003, the game is in many ways very lifelike. It features its own virtual economy, where players work jobs to earn in-game currency (called ISK, or InterStellar Kredits) which they can spend on commodities sold by other players, who often work together as part of a corporation. Commodities travel across the universe along their own unique supply chains; materials are gathered by mining corporations, transported by logistics corporations and processed by processing corporations, before finally being sold to other players on the open market. Every step of the way is paved by players using their own specialised ships and set-ups, maximising their productivity.

Maybe you are thinking – that’s enough about gaming. Why should we be interested in a virtual economy? Surely we have enough economics to worry about without diving into worlds which don’t physically exist! I certainly used to feel that way: beyond my own interest as a spectator of the game’s political and economic events, I wasn’t too concerned about what players did and didn’t do in EVE Online. That was, until it occurred to me how likely it was that EVE Online is a reflection of how those same players behave in the real world.[1]

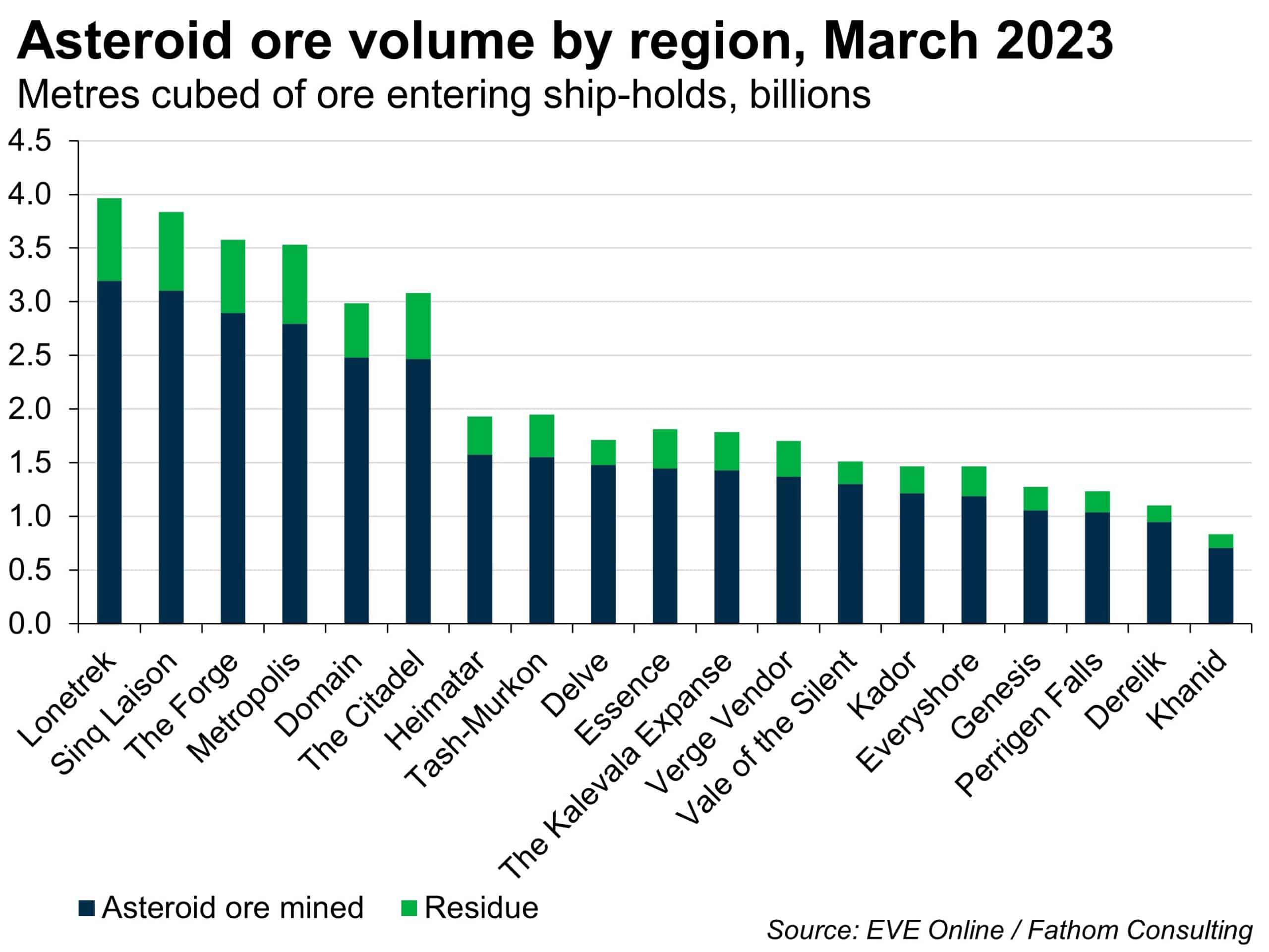

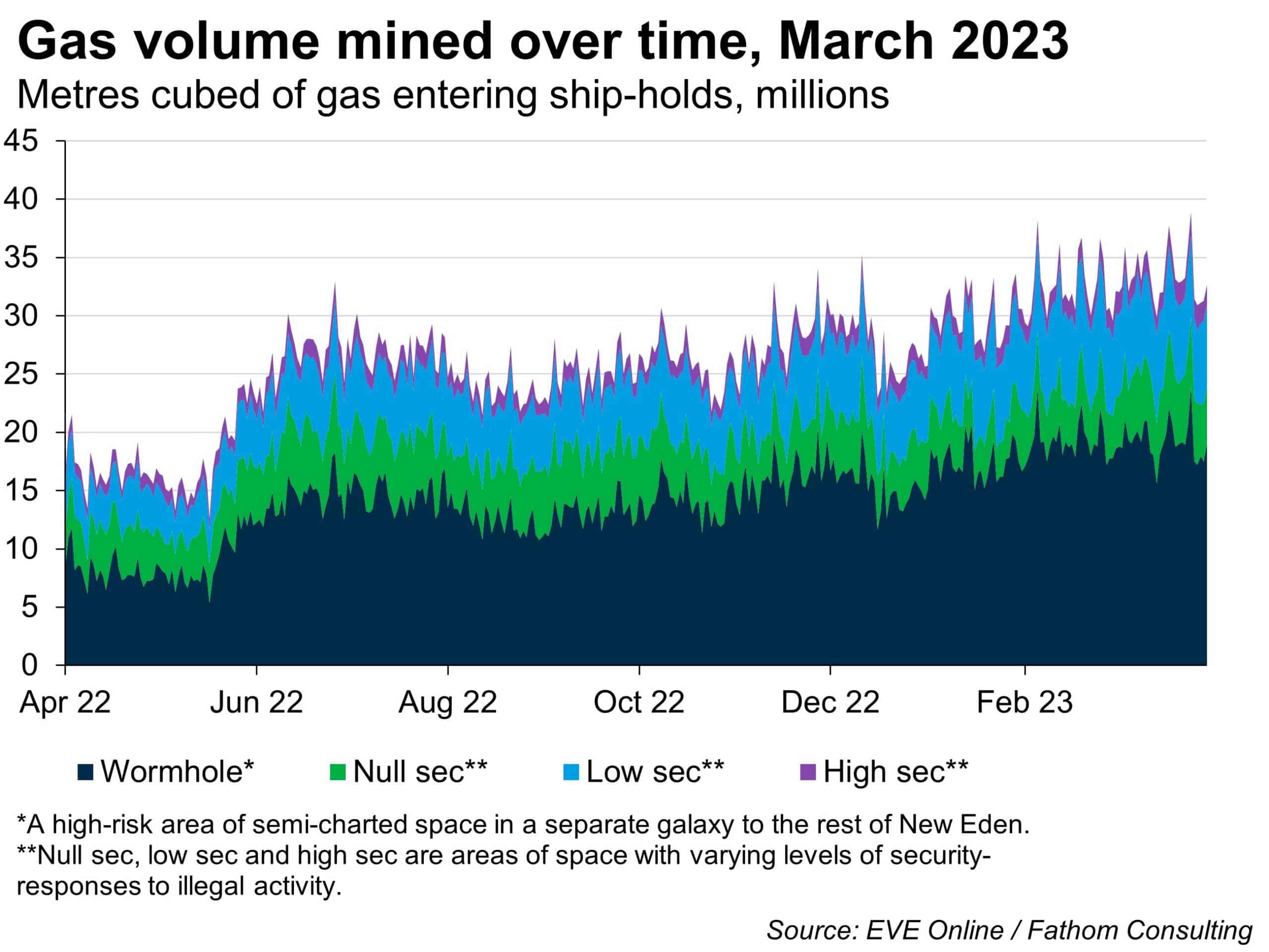

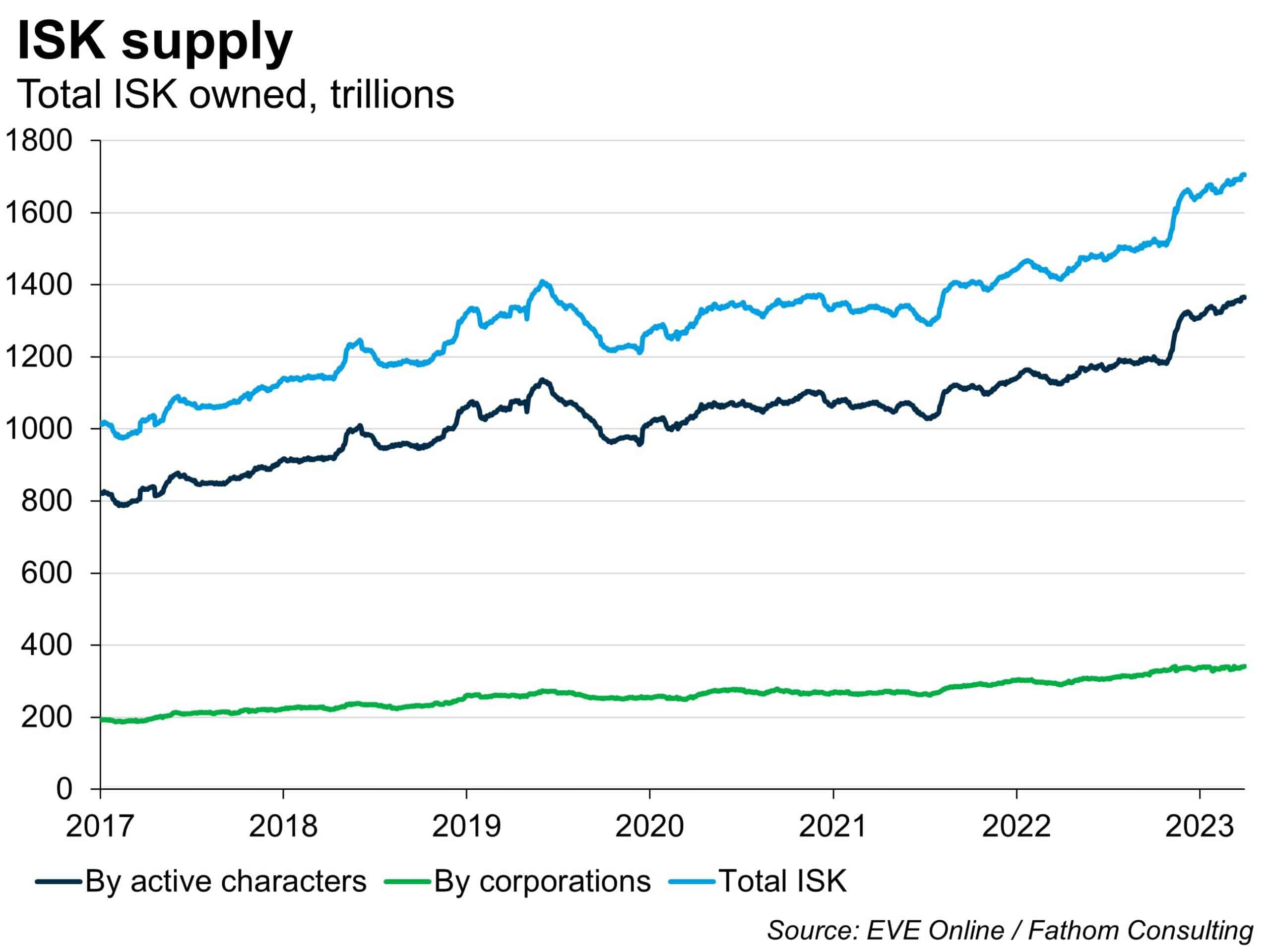

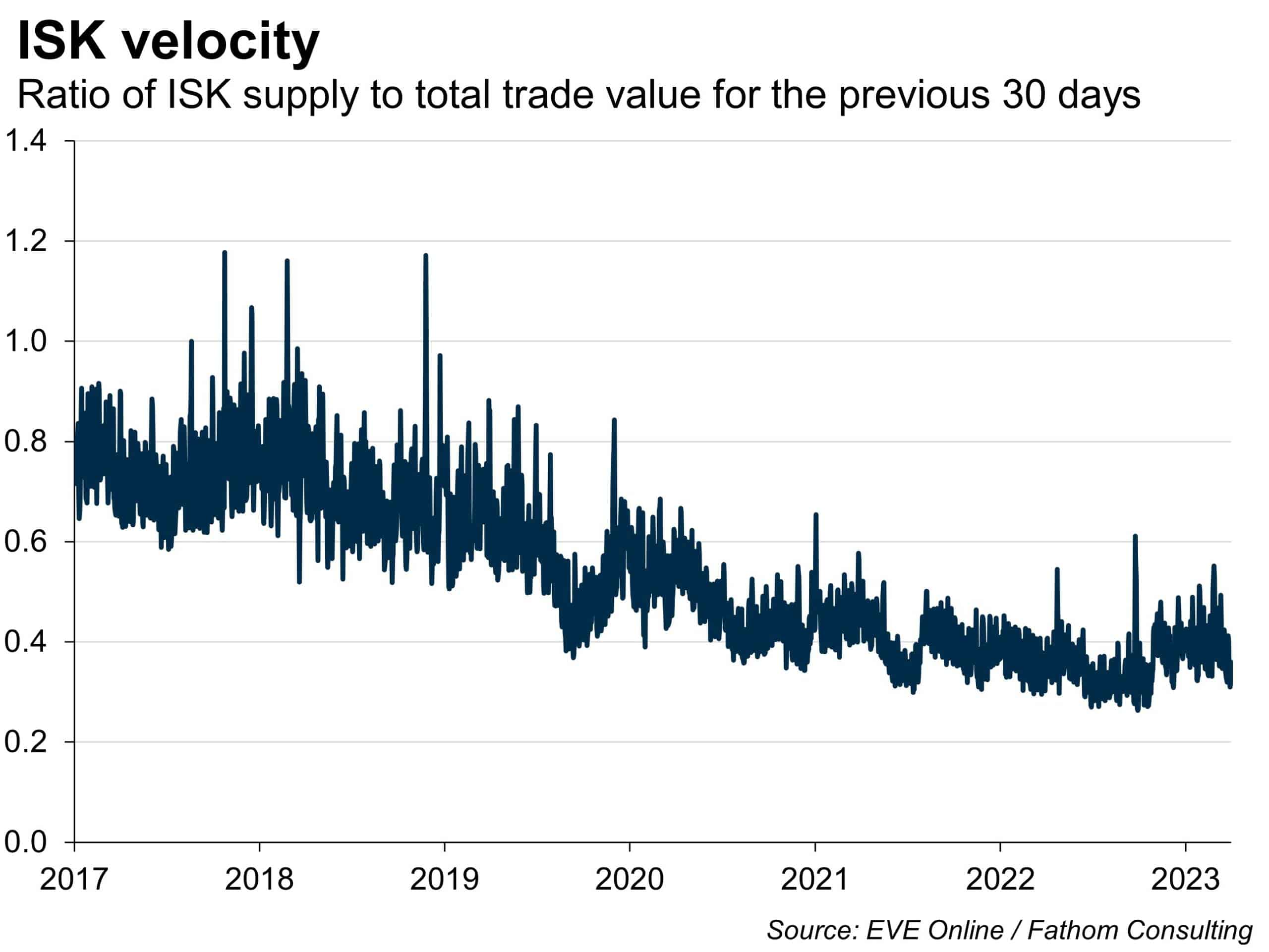

Consider it. Resources in New Eden are scarce due to the time it takes to retrieve and process them. Players must therefore make decisions about their consumption and labour according to costs and benefits. This leads to prices fluctuating according to demand and supply. The resulting trends are even analysed and put into charts in a monthly economic report[2] produced by EVE’s resident economist, Eyjolfur Guðmundsson (yes, they have one). Asteroid ore by volume by region, gas volume mined over time, money supply, and the velocity of ISK are just a few examples of the many moving parts of New Eden’s economy shown in the report. With such a developed and widely interactive economy, should we really disregard the often complex and well-thought-out decisions of players as simply part of playing a game?

The emulation of reality doesn’t stop there: EVE Online also has its own equivalent of real-world nations in its player-driven factions. The aforementioned Imperium is one of these nations; with its own defined borders, military forces, taxation, industries, and chains of command. They even have a form of social safety net, via ship-replacement schemes for when a ship is destroyed in a fleet battle. Empires must balance the need to maximise their tax revenue with the desire to make their territory as lucrative a location for industrial investment as possible, just like real-world nations.

We can even put a real US$ value on the fleet battles fought for the protection of a nation’s interests, by using the grey-market exchange rate[3] for ISK. Using a market price tracker for ISK,[4] we can determine that 7 billion ISK is worth US$45.90. The Imperium’s news outlet[5] (yes, they have one) estimates that 3,404 ships were destroyed, creating a loss of around 22.1 trillion ISK or a whopping US$145,000[6] in virtual space assets from both sides during that one battle! To reiterate: this is a real-world value that was actually lost in the fight. If players so desired, they could have sold and exchanged these assets (albeit, against the rules) into US$145,000 of real money. To think of such a battle as just a fun game between players, rather than a strategic military and economic decision, would be, in my opinion, a gross mischaracterisation. I’ve read far too many real EVE Online stories about war, politics and espionage to believe that EVE players aren’t carefully making decisions to maximise their gain. They literally have their own history book (yes, seriously).[7]

Virtual economies like EVE Online are even designed to share similar market inefficiencies with the real world. Lehdonvirta and Castronova (2014) [8] deftly point out that if we were to continuously remove aspects of the game that create market inefficiencies — factors such as borders, distances, incomplete information — we would completely remove the ‘game aspect’ of the virtual world, and thus no-one would enjoy playing or be willing to pay the subscription fee! This is yet another boon for any curious economist like me looking to draw parallels between EVE’s economy and our own.

Leonid (2020)[9] appears to agree with me. Not only do EVE Online’s economy and players share many similarities with the real economy and consumers, but its capacity for testing and observing is out of this world! EVE Online has perfect data collection, developers have access to statistics regarding every tiny economic interaction; there is a huge emphasis on player-to-player trade; and there are player-made corporations which act incredibly similarly to real corporations, maximising profits by trading, transporting and/or retrieving resources. And to top it all, CCP Games has full control over each and every facet of the economy aside from the very players themselves, enabling us to test whatever imaginary economic scenario we so desire!

Of course, since EVE Online is a game played for enjoyment, players may have slightly skewed attitudes to risk and are likely to make some decisions simply for the fun of it. But, speaking from personal experience playing other games, the majority of a player’s fun comes from optimisation and, well, winning. Economically and violently. So please stand by while I try to convince the rest of Fathom to drop everything they’re currently doing and base all of our future research and conclusions on player behaviour in a sci-fi videogame.

Two Caldari freight haulers (Charons) from the videogame EVE Online. These ships are to be introduced in the Red Moon Rising content patch. This is a real-time screenshot of EVE-Online. Source: Wikimedia Commons / Perplexing

[1] Minus the blowing each other to pieces (to a degree).

[2] https://www.eveonline.com/news/view/monthly-economic-report-march-2023

[3] It’s against the game’s rules for ISK to be sold for real money, and players who are found doing so are permanently banned. Nevertheless, there are many widely-available sites which serve this function.

[4] https://www.playerauctions.com/market-price-tracker/eve/

[5] https://imperium.news/eve-of-destruction-the-titan-massacre-at-m2-xfe/#:~:text=2%3A%2022.1%20trillion%20ISK%20was,the%20battle%20of%20M2%2DXFE.

[4] This uses today’s ISK to US$ exchange rate as opposed to the one from December 2020, but it gives an idea of the scale of the battle regardless.

[6] https://www.empiresofeve.com/

[7] https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262535069/virtual-economies/

[8] https://dlib.bc.edu/islandora/object/bc-ir:109033

More from Thank Fathom It’s Friday: