A sideways look at economics

This week’s TFiF goes gingerly down the rabbit hole of market pricing, using implied expectations about UK Bank Rate as an example. What do investors base their forecasts on, and are they any good at it? You might think that they should devote all of their efforts to a careful consideration of the various bits of publicly available information that ought to influence the MPC’s decision. Well, they probably spend a bit of time thinking about that. But in truth, what matters far more to every individual investor, is what every other individual investor is up to — a point first recognised by the famous UK economist John Maynard Keynes, when he described the act of speculating on financial markets as akin to a beauty contest…

According to an article published online by the Financial Times, the probability that investors assigned to a 25 basis point cut in Bank Rate at the next MPC meeting, to be held later this month, had swung dramatically from around 5% as recently as last Wednesday, to more than 50% by the time the article was posted to their website on Monday. This dramatic reassessment followed dovish speeches by two MPC members who had previously voted to keep interest rates on hold, and much weaker-than-expected GDP data published earlier that morning, which showed that the UK economy had contracted by 0.3% in November.

What should we make of these numbers? I’ve previously written about the forecasting skills of economists when it comes to spotting recessions — they’re dire. But how about investors in UK money markets? Are they any better at predicting changes in the Bank of England policy rate? Not really, it turns out.

Each working day, the Bank of England publishes its own estimate of the overnight indexed swap (OIS) curve, covering maturities out to 60 months. This can be seen as a bet by investors on what the overnight interbank rate (known as SONIA) will average between now and the chosen maturity. The Bank then goes a step further and uses this curve to derive forward OIS rates — effectively measures of what investors expect the overnight interbank rate will be in precisely one month’s time, in precisely two months’ time… and so on. By comparing these forward OIS rates with today’s overnight interbank rate, and by making an assumption that the MPC will only ever move in 25 basis point increments, or multiples thereof, we can try to estimate the probability that market participants assign to various outcomes for Bank Rate.[1] To illustrate, if the one-month forward OIS rate were 20 basis points higher than today’s overnight interbank rate, we might conclude that investors saw an 80% chance of a 25 basis point policy rate hike over the next month, and a 20% chance of no change.[2]

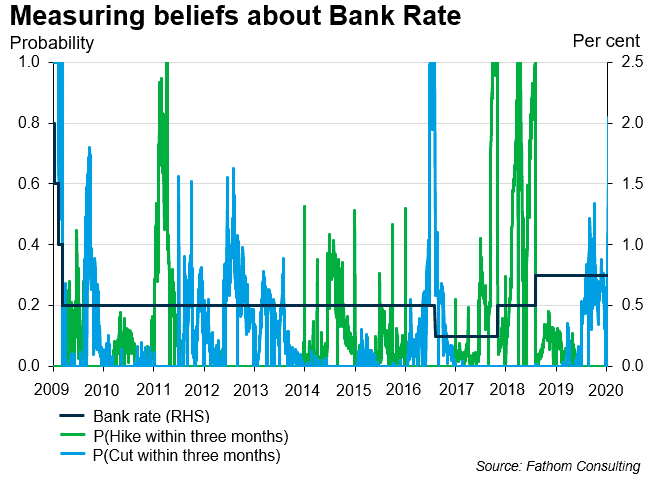

Our chart shows the probabilities that investors have assigned, since 2009, to 25 basis point increases in Bank Rate, and to 25 basis point decreases in Bank Rate over the next three months, alongside Bank Rate itself. One fairly obvious conclusion that one can draw from this is that, over the past ten years, investors have expected far more variation in Bank Rate than the MPC itself has delivered. Investor forecasts have, in short, been excessively volatile. In that respect, investors’ forecasts about the interest rate cycle are the polar opposite of economists’ forecasts about the economic cycle, which tend to be excessively smooth.

What might account for this excess volatility? It’s hard to be sure, but one possible explanation lies in the fact that, strictly, it doesn’t necessarily pay an individual investor to price these instruments according to what, in this case, he or she believes the Bank of England will deliver. Rather they should price them according to what he or she believes that other investors believe the Bank of England will deliver. Or, going one step further, according to what he or she believes that other investors believe, other investors believe the Bank of England will deliver. And so on.

Writing in 1936, John Maynard Keynes famously used the analogy of a beauty contest to describe the incentives facing investors. Imagine a contest where competitors are invited to choose the six most attractive faces from a group of a hundred, with the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most closely resembles the average choice among all competitors.[3]

“It is not a case of choosing those [faces] that, to the best of one’s judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those that average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practice the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.” (Keynes, General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936).

When investors are trying to guess not what the Bank of England will deliver, but what other investors believe about other investors’ beliefs about what the Bank of England will deliver, then we have many moving parts. According to Keynes a game is being played where, at a minimum, each investor is trying to guess how every other investor believes every other investor will react to a piece of news. And it’s perhaps the complex nature of this game, with belief founded upon belief founded upon belief, that leads to excessive volatility in a number of financial markets.[4][5]

So, will the MPC vote to cut interest rates when it meets later this month? It might do. Our forecast for some time has been that the next move in Bank Rate would be downward. The message of this TFiF, essentially, is don’t read too much into the implied probabilities of various outcomes for Bank Rate. They contain very little information about Bank Rate! If the MPC does deliver at the end of this month then, since Bank Rate hit 0.50% in March 2009, investors will have successfully called the direction of the next change in Bank Rate just 59% of the time. So better than a coin toss, but only just.

[1] In March 1999 external MPC member Willem Buiter, who had a reputation for being somewhat contrarian, voted for a 40 basis point cut in the policy rate. On no other occasion has an individual member voted for a change in the policy rate of a magnitude that was not divisible by 25 basis points with no remainder.

[2] We’re making the simplifying assumption that investors will never assign a positive probability to both an interest rate cut and an interest rate hike. This is defensible over shorter time periods, but less so over longer time periods.

[3] Yes, this quote is now showing its age!

[4] Writing in 1966, Paul Samuelson famously observed that “the [US] stock market has forecast nine of the last five recessions”.

[5] Taking a slightly more formal approach than I have adopted in this week’s TFiF, Franklin Allen, Stephen Morris and Hyun Song Shin show how, in a world where there is both public and private information, asset prices will respond excessively to public information. The intuition here is that, in a Keynesian beauty contest, each investor who is trying to second-guess the behaviour of other investors will rationally put more weight on the public information common to all investors than his or her own private information, even if the latter may suggest a very different valuation.