A sideways look at economics

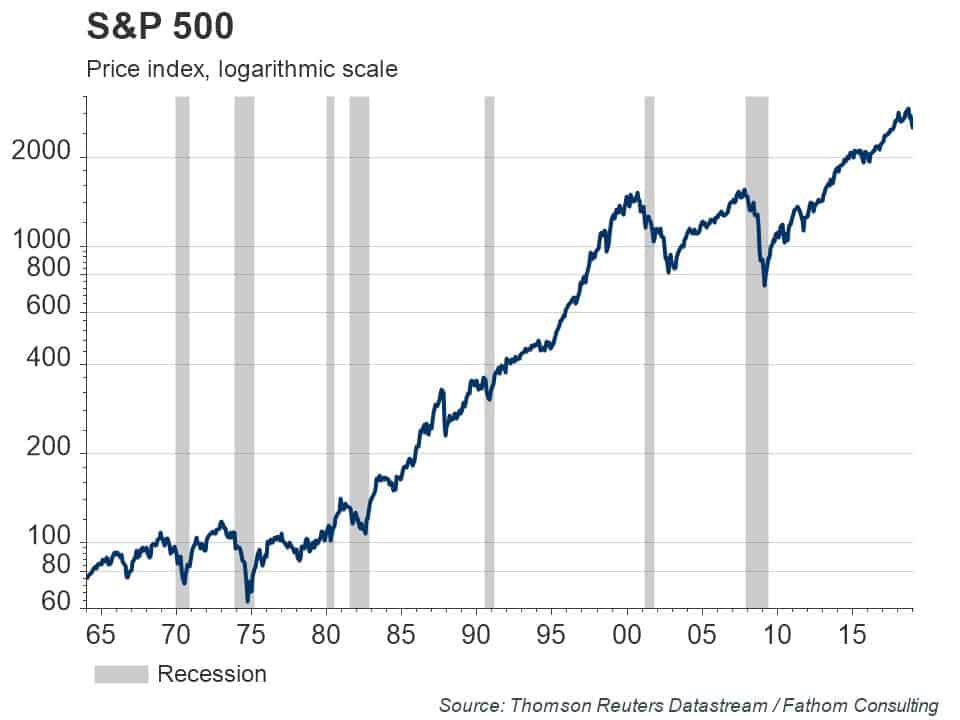

Writing in 1966, Paul Samuelson famously observed that “the [US] stock market has forecast nine of the last five recessions”. Like Aesop’s fabled Boy Who Cried Wolf, equity investors have a tendency to panic too often. That was true back in 1966, and it has remained true subsequently, as our chart shows.

Recessions tend to be non-linear events. Outright economic contractions are rarely preceded by a gradual slowdown; rather growth is often close to trend the year before the crisis hits. Perhaps that is why economic forecasters, too, struggle to identify them far in advance, or indeed even when they are happening. Take the IMF as an example. I pick on that institution only because it’s kind enough to make available on its website every vintage of its twice-yearly World Economic Outlook (WEO) database since 1988[1].

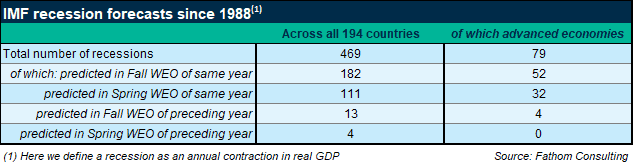

Looking across 30 years of data for 194 countries we find that there have been 469 recessions, which, for the purpose of this week’s TFiF, I define as an annual contraction in real GDP. So they occur, on average, every ten years or so. How many of those did the IMF spot the year before? Just four if you look at the Spring WEO, published in April[2]. Kudos, then, to the IMF economists responsible for Equatorial Guinea (in 2010 and 2015), Papua New Guinea (1997) and Nauru (2018). That’s right. Since 1988, the IMF has never forecast a developed economy recession with a lead of anything more than a few months[3].

And even in the year of the crisis itself, the record is far from stellar: 41% of advanced economy recessions were spotted by the time of the Spring WEO, rising to 66% by the time of the Fall WEO. And like investors, economic forecasters are prone to cry wolf. The IMF has predicted a recession in the following year, where none has subsequently occurred, 24 times in the Spring WEO, and 23 times in the Fall WEO. The signal-to-noise ratio in IMF forecasts is poor, in other words!

In the present context, the above analysis leaves Fathom with something of a dilemma. As clients will be aware, for close to a year we have been warning of a US-led global recession beginning in 2020. Once the Trump tax cuts were approved, and implemented, it became clear to us that, starting from a position where there was little if any economic slack remaining, the US economy was set to grow substantially above its post-crisis trend for up to two years. That would, in our estimation, have left US output almost 4% above potential by the end of this year. Historically, when US output has risen so far above potential, a recession has been more or less inevitable within a year or two. US policymakers, like those elsewhere, have never managed to guide an overheating economy gently back to normal levels of operation without triggering a recession.

When we first made this prediction, we were out on a limb. Now many others have become concerned that a global recession could be just around the corner. Does that mean we’ve got our 2020 call wrong? Surely if policymakers see it coming, they’ll take avoiding action and it won’t happen? That’s possible. Investors have pretty much written off the prospect of any increase in US interest rates this year. If the Fed does sit on its hands, maybe the US economy will keep bumping along the top? On the other hand, maybe the global economy is on the brink of, or already in recession? We may be a year late in our predictions. These and other issues will be debated in our next Global Economic and Markets Outlook, presented to clients in early March.

I’ll end this TFiF by noting that, in the Spring WEO published the year before a major economy recession, the median IMF forecast for growth in the affected country one year ahead has, until now, been 2.7%. In the January interim WEO update, the IMF revised down its forecast for US growth in 2020 to 1.5%.

[1] An IMF paper published in March last year finds that the mean forecast for one-year-ahead growth among private sector economists has typically been very close to the IMF’s own forecast. In that respect, private sector forecasts are, on average, no more or no less trustworthy than those of the IMF.

[2] Rising to thirteen if you count the Fall WEO, published in October.

[3] In the Fall 2008 WEO, the IMF correctly predicted that the German, Icelandic and Spanish economies would contract through 2009. In the Fall 2010 WEO, it correctly predicted that the Portuguese economy would contract through 2011.