A sideways look at economics

Thank Fathom it’s Friday! No doubt, our regular readers eagerly await this blog as a watershed moment in their working week. I can hear the sound of pens dropping, keyboards stopping mid-sentence and the occasional gasp of excitement punctuating the silence of the open-plan office as the weekly TFIF email drops in your inboxes. At Fathom, sending off TFIF also coincides with the beginning of ‘beer o’clock’, our customary post-work Friday drinks. To us, TFIF represents the joint celebration of the end of the week, coupled up with our unique mix of opinions and interests. We certainly love celebrations here at Fathom. But can there be such a thing as too much celebrating?

Perhaps some might be surprised to find out that I think so. At the most basic level, I feel celebrating should be reserved for exceptional events. Doing it too often normalises the exceptional, and devalues the very act of celebrating. A glaring example of this is the proliferation of ‘National (or World) Something’ days. According to the UN, today is ‘World Youth Skills Day’. Important stuff, no doubt. But according to this website, today is also ‘National Orange Chicken Day’, ‘National Gummi Worm Day’, ‘National Be A Dork Day’, ‘National I Love Horses Day’, ‘National Give Something Away Day’, ‘National Pet Fire Safety Day’ and ‘National Tapioca Pudding Day’. Now I’ll admit I’ve been known to secretly stuff my face with gummy worms from my kids’ Halloween stash, and my wife thinks I’ve got hoarding tendencies, but are any of these worthy of being celebrated? I’ll say it: not a chance. Some are just cynical and cheap marketing ploys. I understand the idea of wanting to represent a variety of tastes and preferences, or to raise awareness about important topics with low media coverage, but this is not the way to do it.[1] Not only are these initiatives not worth celebrating, but — to stick my neck out — they are also outright harmful for society.

One pernicious effect comes from blurring the distinctions between historic and momentous events and significantly less worthy causes. Want some examples? Next week, 20 July marks the anniversary of the first moon landing — as well as ‘National Hot Dog Day’ and ‘National Lollipop Day’. Which is more rational: raising a glass to the pinnacle of human ingenuity, or popping the champagne to wash down a hot dog or a lollipop? Except that you don’t need to choose: these events are not mutually exclusive. You could hold a moon landing party with hotdogs and lollipops on the menu and not have to prioritise which should be treated as more important. I find this very disturbing because it creates a casual mental connection between the trivial and the important where there wasn’t one before.

Another negative impact from National Something Days comes from the opportunity they provide to use famous events as decoys. The best way to introduce a controversial, minority-held idea is when the majority is distracted. Politicians do this all the time by slipping an unpopular bit of policy within an unreadable, 10,000-word document, from which only the most popular ideas are spoon-fed to journalists. Here is a tongue-in-cheek example of this: 8 May is when most Europeans celebrate the end of Second World War hostilities (Russians celebrate the day after), arguably one of the most important dates in modern times. In 2022 it was a particularly busy day in the calendar, with the frankly questionable ‘No Sock Day’ and ‘World Donkey Day’ flying under the radar behind the WWII armistice, not to mention the culmination of ‘National Lawyer Well-being Week’ (I can certainly see how that particular profession might not have wanted to draw too much attention to this celebration).

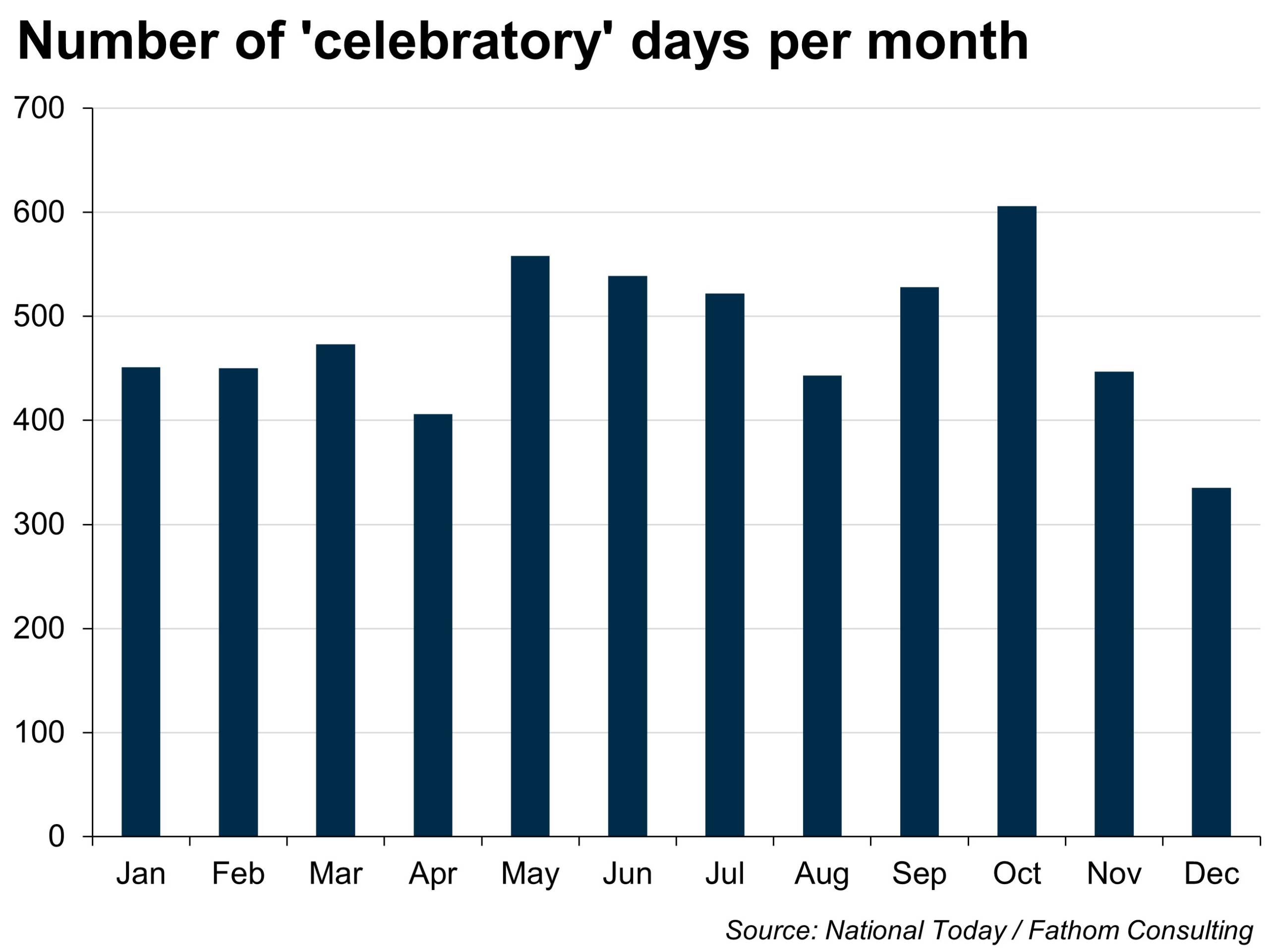

I can hear some counter-arguments already: if you don’t like any of these celebrations, just ignore them. But ignoring the problem is what enables it in the first place. As economists, we are trained to distinguish causation from correlation, signal from noise. Even to the professional eye, it is not easy to tell apart the important from the irrelevant, particularly with the proliferation of information and ever-increasing ease of dissemination. Flooding the calendar with almost 6000 celebrations (see chart), under the guise of a bit of fun, is a clear example of this trend.

Having days with no celebrations makes those days with something to celebrate more important. Celebrating nothing for a while creates a sense of anticipation, which leads to deeper reflections about why those events are important and worthy of being celebrated, creating a virtuous cycle of reinforcement. Conversely, celebrating all the time for all sorts of reasons floods the system with noise, it trivialises the important by crowding out the strong signals, leading to a more chaotic system with fewer reference points. It is also arguable whether we need more representation and diversity in our celebrations. We already have birthdays, the ultimate expression of individualism: everyone has a day when they celebrate themselves with their unique flaws, strengths, struggles and victories. I can also attest that the birthday parties of complete strangers are well worth attending (ideally with an invite, but I hear there might be ways around this) and, frankly, I’d far rather celebrate a total stranger than, say, ‘World Emoji Day’ (coming up this Sunday, for those interested).

Awareness of the risks of losing sight of what is really worth celebrating is relatively low. This blog is an attempt to flag this danger through a bit of economic satire. However, comedy is no panacea. For example, an episode of South Park was once infamously credited with inspiring the institution of ‘Kick A Ginger Day’ (even though there was no reference to such a day in the episode in question), which led to deplorable cases of actual physical abuse. Disappointingly, public opinion mainly blamed South Park for provoking the assaults, and never scrutinised the role of these confected days of celebrations in normalising and enabling the perpetration of such heinous acts.

In my opinion, these national nothing days (the actual ‘National Nothing Day’ fell on 16 January this year, same as Martin Luther King Jr Day… so, so wrong!) are a broader symptom of a society-wide identity crisis, worsened by the slow erosion of independent critical thinking. I’m not going to digress too much on how we’re losing the capacity for individual thought, particularly as it is Friday afternoon, but equally I don’t want readers to get the wrong impression. Just like criticisms, genuine celebrations ought to be rooted in a journey to understand, to accept and to improve on our failures, mistakes and imperfections. We should celebrate (and criticise) because we know what it takes to formulate an original thought — by elaborating from data, listening to different opinions, and from experiencing failure and success. We should push back against the notion that a top result from a search engine constitutes objective truth, and acknowledge that there is more to reputation and credibility than the number of likes, views or followers on social media platforms. Seems obvious — and yet we are increasingly happy to allow the convenience of oversimplified measures of objectivity, coated in a thick layer of mediocrity and noise, to redefine our reality and what we will eventually accept as ground truths.

As a consummate pop culture trend follower, a couple of days ago I caught up with the film Inception, only 12 years after it was released. I liked it, especially the idea of the totems: little somethings that only the user intimately knows — the weight, the imperfections — as a way of telling apart a dream from reality. Perhaps, we should think of celebrations as our own unique totems. Remaining in charge of why and how we celebrate will allow us to control reality on our own terms, and will nurture our critical thinking. Similarly, I like to think that TFIF is Fathom’s totem: we choose to celebrate Fridays and our diversity in interests and styles as a statement of our independence, a key aspect of the corner of reality we inhabit.

[1] If you are reading this before holding your wild ‘National Be A Dork Day’ party, please do send a pic of the festivities and an invite to next year’s bash. I promise I’ll make amends, attend in 2023 and cover it in a subsequent blog post.

More by this author

Ground control to Major Fathom