A sideways look at economics

Becoming a new dad, which I did for the second time a few weeks ago, is a somewhat surreal experience: time passes at a different speed, perspectives change, survival mode kicks in and the mind wanders. I’m back at work now and reconnecting with the practical aspects of my life. For today’s blog, I merge the new dad and the economist mindsets, and share a few thoughts.

Money is nothing

Childbirth is the most stressful experience I know, and I’m not even the one doing it. They say that the second birth is typically easier than the first, but for various reasons that wasn’t the case this time round. I won’t delve into the details other than to say that when certain curveballs of nature were thrown at us during labour (thrown at her, of course, but I was there doing my best to help and be supportive), I was worried about the life and health of my wife and baby. On reflection, I realised that there was no amount of money I would spare to ensure their wellbeing. Equally, no amount of money would make a single bit of difference in that moment.

Money is everything

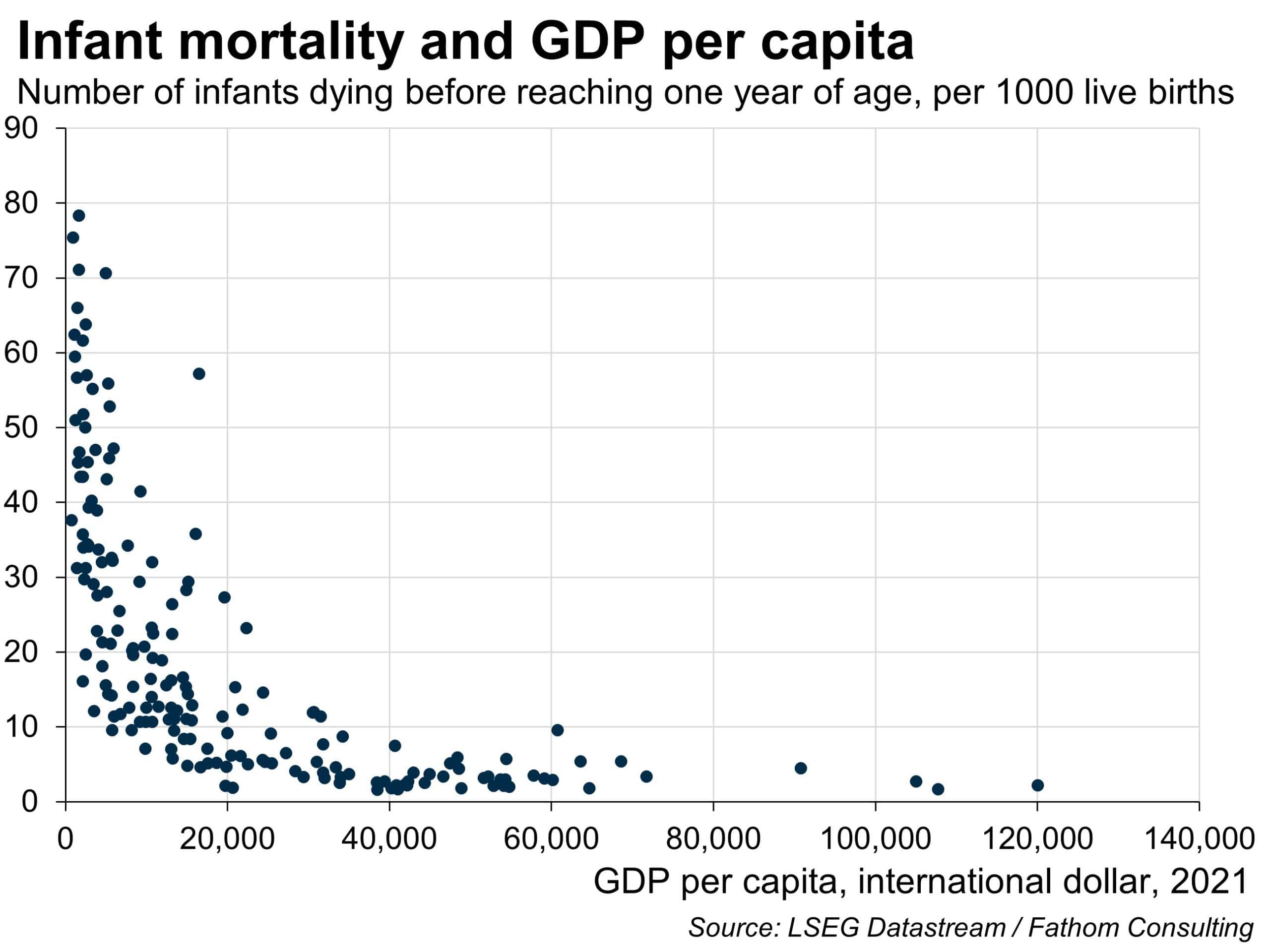

Mentioning money in such a context is ridiculous in some ways: doctors do not accept money in the moment to decide how well they are going to deliver a baby, thankfully! Some might say that even mentioning money in this context is distasteful. But money is an important yardstick to measure the importance which people attach to things, and that’s what economists do. So there are three reasons I think a money-related reflection is valid. First, I think that most humans have at times felt that they would do anything, give anything, for something important to them. Second, outcomes can be explained by money whether we like it or not (see chart). Third, health economists (I am not one) need to put a monetary value on life as there are finite resources with which to save and improve lives.

Love the NHS

Shortly after my son was born, I was overcome with emotion. The efficiency of the NHS staff, the competence of the doctors when it really mattered, was incredible. The work they do daily is incredible. Respect. Their actions literally save lives every day and may well have been the difference between the life and death of my son and possibly even my wife. When I told this to one of the doctors who helped deliver my boy safely, she seemed almost shy or embarrassed to accept such gratitude. Humble. Beautiful.

Don’t love the NHS

As someone who has lived in various countries, to me there is a strange attitude towards the NHS in the UK: people complain about its numerous problems, but simultaneously love it and get outraged when anybody dares to criticise it (complaining is not criticising). I think that, rightly, people look nervously at the healthcare system in the US, which spends so much for such poor outcomes, and fear that model coming to the UK. I would certainly be against that.

My experience is that for the big things the NHS is great, but for other things it can be poor, and should be improved. For example, some of the admin was terrible: someone else’s birth notes were given to my wife after her birth. There were great midwives and a few bad midwives. Don’t underestimate the importance of midwives. I don’t have the numbers, but I feel that they should be paid more for the essential work they do – and the good ones should be paid more than the bad ones. Part of their pay could be linked to patient satisfaction. This would raise the quality of care and help attract (and keep!) the better-quality staff.

Don’t answer impossible-to-answer questions

One unexpected question my wife asked when discussing the tricky childbirth over dinner this week was, if faced with a choice, who would I choose to save: my son or her? Obviously, there would be no benefit to me from answering this question, even if I knew the answer. Equally obviously, I turned the question on her: and I told her not to answer it either, because I knew who she would choose — especially if the question was between me and our two-year-old daughter (she would choose our daughter, even if I think she would be somewhat disappointed at losing me). The different feelings we associate with children and partners are fascinating. I take this slippery slope no further.

What sort of world do we live in?

I genuinely think about this quite a lot: what sort of world am I bringing my kids into? There are so many beautiful things in it – places, people, concepts, etc. The intricacies of nature are awe-inspiring. But equally, there are so many problems and issues, many of which I am required to think about for work (climate change, war, etc) and some of which you can see daily. Focus on the problems too much? Boring and a killjoy. Don’t focus on the problems? They will just keep getting worse.

What sort of world do we want to live in?

I love the pureness and simplicity of kids and their logic. I can imagine taking my kids on holiday to a place like Indonesia in a few years’ time and having this conversation:

- Wow those corals and fish were so beautiful today, Daddy!

- Yes, they sure were. Glad you enjoyed it. Let’s enjoy this moment because by the time you have kids they will all be dead.

- Why will they be dead?

- Because global warming will heat the water so much that the corals will die and the fish will go away. [1]

- What’s global warming?

- The world is heating really fast due to the things that humans do, like the fuel burnt on the plane we took to get here.

- Why did we take a plane to come here?

- Because a boat would have taken too long and we wanted to see the corals and fish.

- But the corals and fish are going to die.

- Erm…

I don’t want to be a killjoy and I am not going to stop flying. And I plan to take my kids to the beautiful places I have been lucky enough to visit. Equally, I have tried to reduce the number of flights I take due to their contribution to global warming, and I have worked on a project which explores ways to encourage the decarbonisation of aviation. These are two tangible things that I have done, that could make things better, or at least less bad.

Our family flight to Indonesia won’t specifically be the thing that kills the coral, although the accumulation of things that we humans have done collectively (especially privileged people like me, more than most in this world) are doing just that. I therefore want to be able to look my kids in the eye one day and say with meaning that I have taken some actions to reduce my own footprint, and theirs; and to contribute to the economic system in a way that makes it easier and less costly for others to do the same. Doing my bit to improve the system could be much more impactful than any actions to reduce my family’s personal carbon use, but if I don’t do that too I would be a hypocrite. So I try to remind myself of this, like I remind myself that climate change has far more dire consequences than the ability of my kids and their kids to enjoy the wonders of coral reefs while on holiday one day.

Nature versus science

During the birth process many things are natural. In fact, I can’t think of anything more natural than childbirth itself. Equally, as described above, childbirth can be influenced by humans and by resources (sounds more palatable than money). There is something to be said for accepting things the way they are in life more generally. We can’t control everything, and personally I would not want to. But so many things in life and this world are within our control, or ability to influence. I bet individuals could achieve better health and wellbeing outcomes in many situations by just accepting things and thus reducing stress levels, with all the physical and mental health benefits that brings. That probably wouldn’t be hard to prove scientifically. In other words, science could tell you to stop thinking about science. Some controlling: good. Too much controlling: bad.

These reflections are echoed in spiritualism, and even religion. The well-known Serenity Prayer says: “O God, give us the serenity to accept what cannot be changed, the courage to change what can be changed, and the wisdom to know the one from the other.”

Don’t do a renovation during pregnancy

Just don’t.

Make sure your renovation is finished before your baby is born

Just do.

Enjoy the ride

There are many things that parents can and do worry about. Is this fine? Is that fine? They start well before birth and continue for the rest of your life. I suggest you control what you can, and let the rest be. Stepping back, I think a parent’s job is never really done. Yes, things may change and some things get easier over the years; but equally things may get more difficult in other ways and there will be new things to worry about all the time. Don’t think too far in the future. Enjoy the here and now, and the journey, whatever it throws at you. Happy Friday.

[1] https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/why-are-coral-reefs-dying; https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/coralreef-climate.html

More by this author