A sideways look at economics

At the age of 32, my other half is retiring, and he thinks I should too. At least, that’s what this morning’s drive to the station implied. Sure, we’ve discussed the joys of being footloose and fancy free, exploring the world and wearing our hair in dreadlocks, but I didn’t really mean it! My response to this morning’s ambush was silence, which I suspect spoke volumes, or, at the very least, made my true feelings a little clearer.

I’m not alone in saying one thing but meaning and doing another. Most of us do it, particularly when it comes to painting a picture of ourselves — be it on dating sites, job applications or meeting someone new. How many of us still list ‘travel’ as our top ‘personal interest’ — squeezed onto the bottom of a CV or submitted to the advert-generating algorithms of Instagram? In reality though, and according to the number of worldwide Google searches, we’re just as likely to research the next box set to binge-watch as we are to check out our next big holiday destination.

Based on this week’s most Googled terms, other genuine interests which are just as unlikely to make their way onto a CV, relate to catching the latest scoop on Wayne Rooney’s love affair (that man is punching, has he lost his mind?), pining for the next instalment of everyone’s favourite bad boy Brummies (the Peaky Blinders), and dogs (well, they are better than cats!).

Although inflated CVs and falsely flattering first impressions are relatively harmless (resulting in mild embarrassment when forced to reveal that I watch endless clips of puppies on YouTube instead of my stated preferences, and no, I don’t know where Bhutan is), being economical with the truth can lead to far bigger problems — as China has discovered.

Under Deng Xiaoping’s rule, the national approach was to say very little that could lead to judgements about the nation and its policies. In other words, to lie low. But all that has since changed, and Xi Jinping’s openly nationalistic stance, accompanied by exaggerated claims of success, has been blamed for hardening the anti-China rhetoric coming from the US.

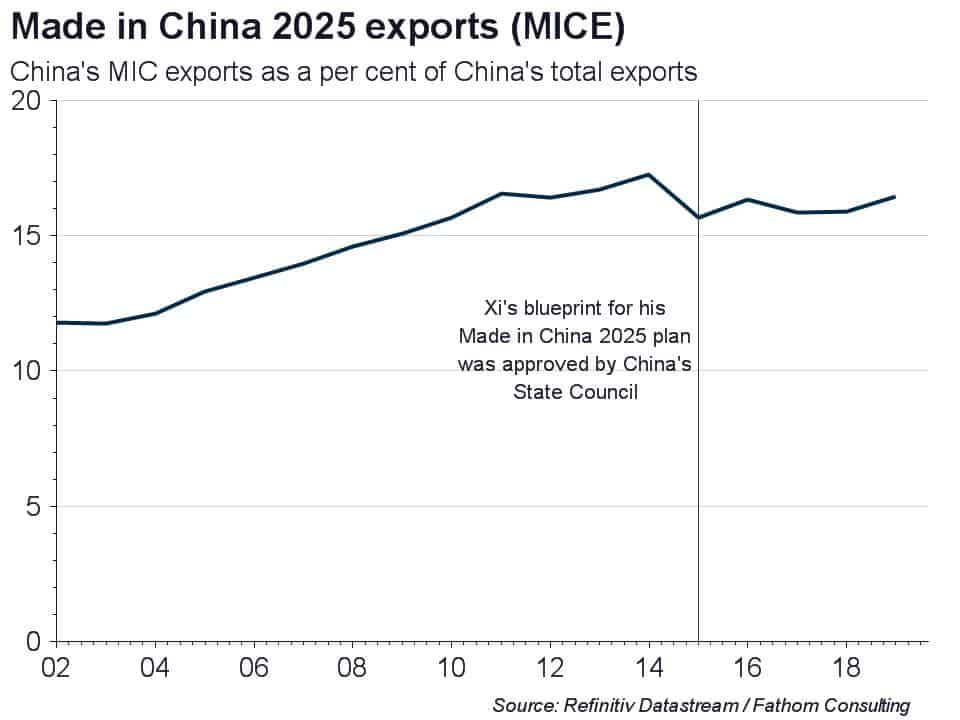

An obvious example, and one that we painstakingly analysed at the time, was the state-driven fanfare around President Xi’s ‘Made in China 2025’ (MIC 2025) plan, which boasted about China’s transition from low-end manufacturing base to high-tech powerhouse. Needless to say, his vision and the high-tech sectors it relates to have been in the crosshairs of the US administration’s strategy.

That is despite our finding that China’s efforts to move up the value chain — by which we mean upgrading the economy from traditional industries reliant on low-skilled workers towards more advanced and technology-driven growth — predate President Xi. In fact, the idea goes all the way back to the 1980s, and yet independent data on China’s progress remain patchy at best.

Here at Fathom we created a tailor-made database known as RiCArdo, to fill in the gaps.[1] It whittles down over 1800 different categories of goods exports into just the high-tech sectors targeted by MIC 2025, with data on export values, shares and country specialisation for around 200 countries and regions.

From this, we can identify China’s true progress in overhauling its enormous manufacturing base. Our Made in China Export indicator (MICE) shows that it has stalled. No wonder China’s policymakers have reverted to Deng Xiaoping’s tactic of lying low, downplaying the plan as part of the nation’s overall growth strategy. Some might even say, staying quiet as a mouse.

[1] To find out more, or to subscribe to Fathom’s RiCArdo — our global database of leading nations in high-tech sectors — please contact Joanna Davies.