A sideways look at economics

For a (neutral) football fan, last week was truly exciting. Both Champions League semi-finals produced major surprises. Liverpool FC beat FC Barcelona to progress to the final despite having lost the first leg 3-0. Tottenham Hotspur beat Ajax Amsterdam in dramatic fashion, scoring three goals in the second half — the last one in the 96th minute — despite having lost the first leg and having been two nil down at half time. People who, against the odds, went to the pub, or in Tottenham’s case, didn’t leave it after the first half, were rewarded. Owners of Ajax Amsterdam shares less so. Their price dropped more than 18% (relative to the broader Dutch market)[1] the next day.

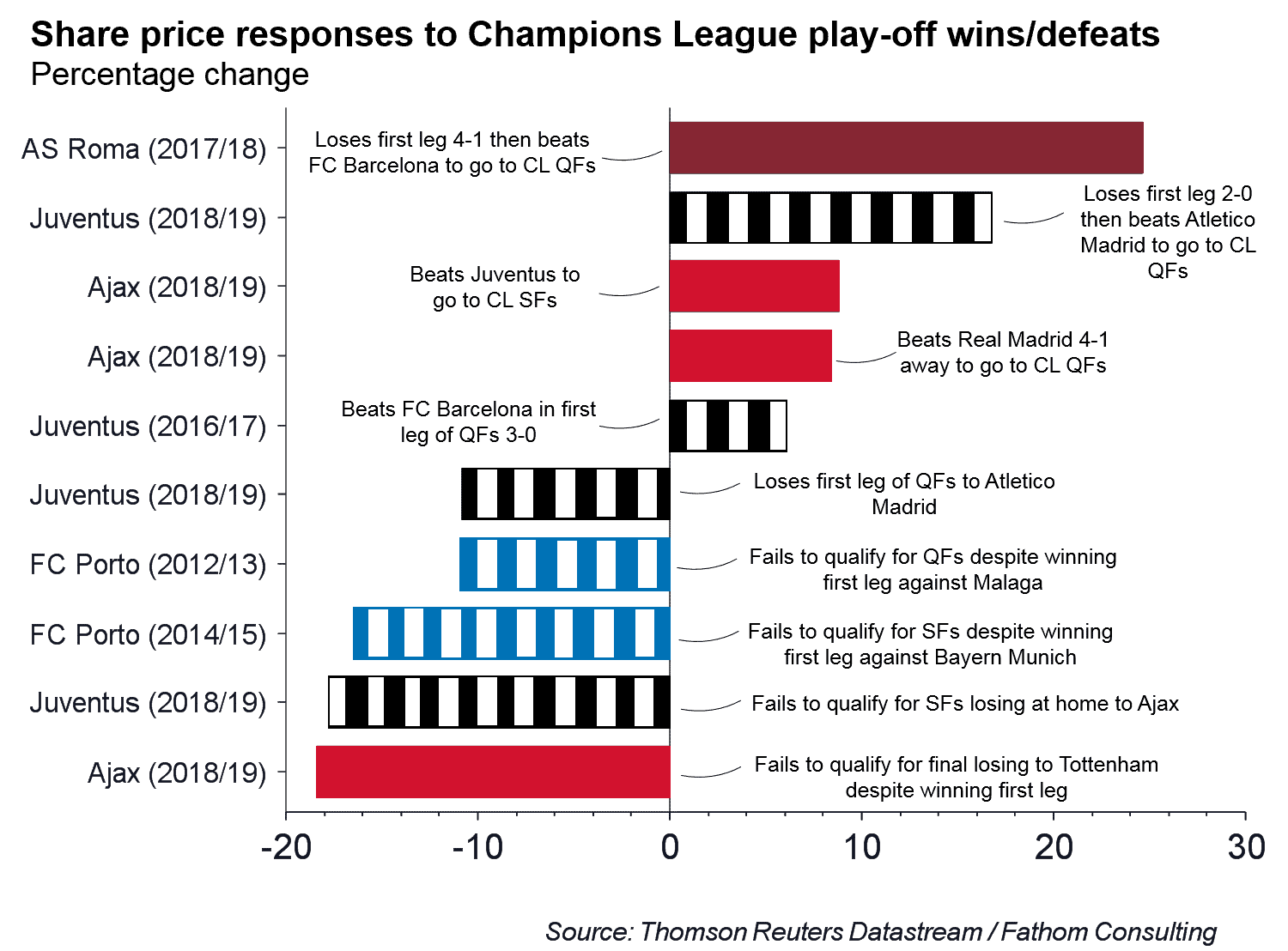

Indeed, that was the largest drop following a Champions League play-off defeat among the thirteen clubs that are publicly listed and have regularly been participating in that competition since at least 2010.[2] The next largest was the drop in the price of Juventus shares after that club unexpectedly lost to Ajax in the previous round. Ajax’s share price rose by close to 9% the following day. A relatively small gain compared to the 25% increase in AS Roma’s share price following the team’s win against FC Barcelona to go through to the semi-finals despite having lost the first leg 4-1 in last season’s Champions League.

Progressing to the next Champions League round implies large increases in revenues and profits. As with other corporations, the share price of any football club ought to reflect future earnings. Allegedly, reaching the final has earned both Tottenham and Liverpool more than £100 million this season. So, progressing through the Champions League play-off rounds could potentially increase the earnings outlook of a football club materially.

Before make-or-break games whose outcome could potentially boost earnings, share prices will reflect shareholders’ expectations of the corresponding team’s chances of winning the game. Specifically, shareholders’ odds can be gauged by the share price increase relative to the broader domestic market the day after a Champions League play-off game. For example, a large jump in a team’s share price in response to a win would imply that shareholders had judged the winning team to be the underdog before the game.

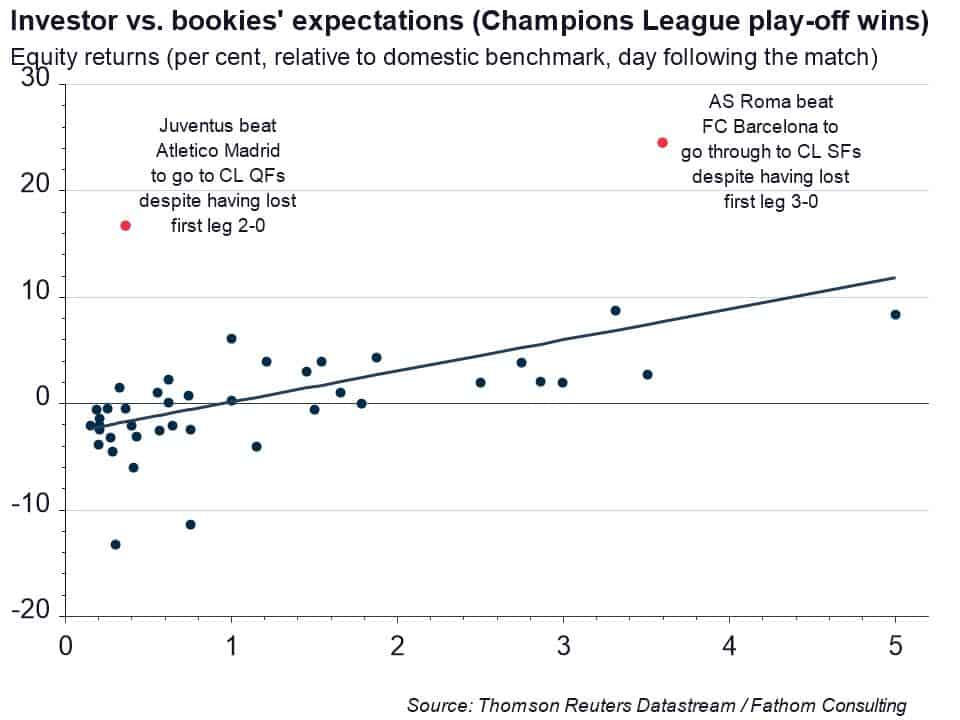

How do shareholders’ expectations compare to those of bookies? Bookies’ expectations of a publicly listed team winning a Champions League play-off game are derived by the relative pay-off for the two competing teams. That is, a value of one would imply that both teams are judged equally likely to win, while a value greater than one would imply that the publicly listed football team is the underdog, according to the bookies.

Using these two measures, the following chart compares bookies’ expectations with those of shareholders for Champions League play-off games that the publicly listed team won. As you would expect, there is a clear positive relationship. The more bookies judge a team to be the underdog, the larger the increase of that team’s share price tends to be in response to a win. Bookies and shareholders agreed that a win was relatively unlikely.

Overall, the market tends to operate quite well. That said, shareholders really didn’t expect Roma’s comeback against Barcelona and Juventus’s turnaround against Atletico.

Interestingly, share prices of favourites tend to fall, even though the team lived up to expectations (the area for values smaller than one on the horizontal axis in the chart below). One explanation might be that shareholders tend to fully price in wins by the favourite.

So, if you want to bet on the favourite, you’d be better off going to the bookies. How about risky bets? If you were a real football expert, or an Ajax fan, and had bought £100 worth of the club’s shares on the day of the team’s first play-off game against Real Madrid and sold them the day after the defeat against Tottenham last week, you’d have earned £25[3] (after having peaked at a £64 gain the day before the match). If, instead, you’d split up your £100 to bet an equal amount on the maximum possible seven remaining games, you’d have earned £141 — more than five times the winnings via the stock market. This isn’t surprising, as stock prices reflect a variety of corporate and economic factors, while at the bookies you bet on the outcome of a single game. That is, potential losses are higher when betting via the bookies. Indeed, you’d have lost half your bets, including the very first one. Risk and reward.

In any case, isn’t witnessing a great football game reward enough?

[1] All share price movements in this note refer to changes relative to the broader domestic market.

[2] Besiktas JK, Galatasaray SK, Fenerbahce SK, Borussia Dortmund, Juventus, SS Lazio, AS Roma, Ajax Amsterdam, SL Benfica, Sporting CP, FC Porto, Celtic FC and Manchester United FC.

[3] Ignoring exchange rate movements.