A sideways look at economics

When we think of pirates many of us probably picture something out of the Pirates of the Caribbean films, or a figure like Captain Hook. Perhaps your imagination supplies you with a corsair who has a peg leg, an eyepatch and an annoyingly verbose parrot perched on his shoulder?[1]

However, both pirates and piracy as a concept are far more diverse than Western popular culture would suggest. Their history stretches back to the Sea Peoples of the 14th century BC, takes in the Vikings[2] of the dark ages and the centuries of attacks on shipping in the South China Seas, and remains still alive today with activities in and around the Gulf of Aden.

pic: Zoltan Tasi, Unsplash.com

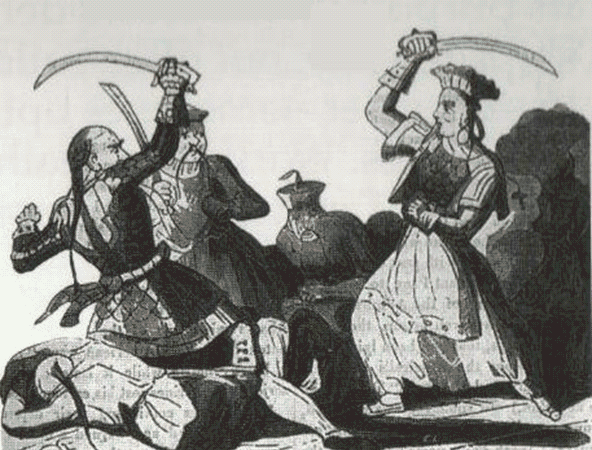

The scope of pirate operations varied — while activities in the Caribbean in the 17th-18th century were usually independent joint ventures with crew size anywhere from 30-100 people, the Guangdong Pirate Confederation led by the pirate queen Shi Yang (who is better known as Zheng Yi Sao[3] in the early 19th century counted nearly 400 ships and up to 60,000 crew. Indeed, anyone who’s downloaded music or films illegally can be counted as a pirate (the author would like to invoke the privilege against self-incrimination here).

Shi Yang | Anon, Wikimedia Commons

The typical pirates most of us picture are loosely based on those operating in the period called The Golden Age of Piracy, lasting from around 1650 to 1720 and predominately concentrated in the areas in and around the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic.[4] Pirate ventures were often made up of groups of ex-navy and merchant sailors seeking better fortunes and more freedom. Ships were organised in a democratic manner, with a captain chosen by majority voting and loot quotas decided by a separate quartermaster to ensure fairness.[5] Nor were pirate ventures necessarily always illegal (at least in their homelands), with pirates often operating as privateers for government officials.

By the time of the early 18th century piracy as a career choice was in a strong decline for Western sailors as the initial surge in pirate recruitment and activities following the signing of the treaty of Utrecht (ending the War of the Spanish Succession) led to a crackdown by European governments.

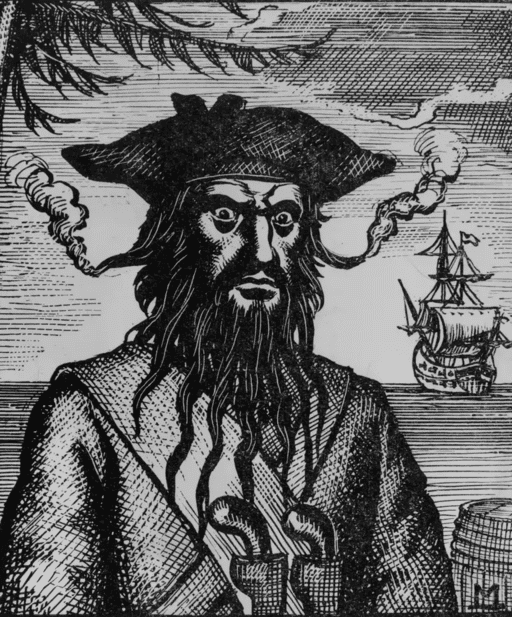

Many pirates whose names we still know today were also famous in their own time, with stories of their exploits and brutality inspiring fear, but also envy. However, for every Henry Every, Blackbeard and Levasseur there was also your everyday average Joe Pirate. How could this representative pirate expect to fare economically when ‘going on account’? [6]

Ill-gotten gains

In order to examine this question we’ll avail ourselves of the financial concept of expected return: i.e., the amount of profit or loss an investor can anticipate receiving on an investment. Except in this case the investment is life as a pirate, or rather, a pirate venture. Mathematically we can define the expected return as, where E[R] is the expected return, Ri is the return in scenario i, Pi is the probability of scenario Ri occurring and n is the number of scenarios. For ease of calculation we’ll also assume that there are just four possible outcomes:

1. Capture and subsequent execution (usually by hanging) by authorities, aka ‘a dance with Jack Ketch’

2. No loot, aka ‘No prey, no pay’

3. Hard to share/sell loot (e.g, food, spices, candles, soaps etc.), aka “Aaaargh, ’tis burdensome to buccaneer!”

4. Top tier loot (e.g., gold, silver or gems), aka “Blow me down and shiver me timbers! Port Royal here I come!”

For those familiar with probability distributions, scenario 1 and 4 can be classed as our tail risks, less strictly defined as the risk (or probability) of rare events. [7] It is debatable just how rare it was to be captured and executed, however, especially towards the end of the golden age. This means that our pirate is probably dealing with a fat left tail risk, and that we’re redefining the tail risk to mean ‘worst versus best case’ rather than ‘rare’.

We now need to find some values for the returns in each scenario, and quite quickly run into our first problem: what is the return of being dead? Maybe the inverse value of being alive, but how do we measure that? Well, economics uses various methods for estimating this, but for the purpose of this TFiF it seems a bit over-zealous to try to find the statistical life value of the 17th-18th century pirate. So, we’ll do what economists do best and assume away this problem by giving our pirate the opportunity to bribe his captor in scenario 1 and assume that he would always pick this over being executed. Let’s assume the cost of bribing the official is one year’s salary and that the salary in question was that of a merchant navy sailor in the period, around £4 per month, or £680 in today’s value, using the Bank of England inflation calculator — so for a year, £8,160.

In our second scenario we’ll set the return to zero. This is simplifying things somewhat, as there would have been costs associated with setting sail: food and other supplies, as well as depreciation to the ship and weapons. Note we’re ignoring the cost aspect in all scenarios.

pic: Elena Theodoridou, Unsplash.com

For the return in our third scenario, several angles have been explored. Extensive internet searches into variations on ‘average cargo value of merchant ships in 1700s’ sadly yielded no easily usable results. Equally extensive searches into ‘taxes on merchant ships and/or insurance values’ produced an equal result. We could just assume a value somewhere between the values for scenarios two and four, but this seems a bit defeatist. So instead let’s assume we’re dealing with a West Indiaman (a merchant ship in the western colonies) and that it weighs c.1,000 tonnes in all. Merchant ship crews were often quite limited to allow for more cargo, plus the weight of guns, but we’ll assume a crew of 50 at an average weight of 80kgs per person. From navy food ration logs [8] we can estimate total weight of provisions per person per week at around 37kgs: with length of sailing time from the Caribbean to England of around 6 weeks [9] this gives a total weight of around 11 tonnes for food and drink. Given the risk of attack by pirates and privateers the ship would also be armed with guns or cannons: we’ll assume twenty 24-pounder long guns (slightly fewer than a lightly armed navy frigate [10]) weighing in at 2.5 tonnes per cannon; with ten shells per cannon at just above 12kg each, [11] this gives an artillery weight of 52.4 tonnes. Finally, we’ll say that the ship itself weighs 350 tonnes, [12] leaving room for about 582 tonnes of cargo — nearly 3 blue whales. We’ll further assume that the ship is carrying an equal combination of tobacco, molasses and candles. Finally we’ll assume that our pirate is not travelling all the way to Europe to fence the stolen goods, but rather will sell these in North America, [13] giving a total value of about $104,000 in 1760 terms and $4.2 million in 2023/2024 terms, [14] which with today’s exchange rate equals roughly £3.3 million, or £33,343 per pirate (with a crew of 100).

In the fourth scenario we’ll use the average estimated treasure value of three of the most successful pirate attacks committed during the golden age; Henry Jennings’ looting of a sunken Spanish treasure fleet (1716), Henry Every’s capture of the Mughal fleet’s prize ship (1695) and Taylor, Levasseur and Seagar’s capture of the Portuguese ship Nossa Senhora do Cabo (1721), and calculate this into today’s pound value using again the Bank of England inflation calculator. Assuming equal division of the bounty by crew (although probably there would have been some differences in shares) and a crew number of 100 this gives a return of nearly £813 000.

Reckoning the odds

So we now have our four expected returns, – £8,160, £0, £33,343 and £813,000. But what about our probabilities? This is calculated as the ratio of number of favourable events by number of total events, so in the case of scenario 4 for example, we can say that we have three favoured events, matching the three events we got the return from, but what about the total number of events? Some more assuming [15] gives a total of 190,400, and therefore a very, very small probability of the scenario 4 return.

Blackbeard with his sidelocks on fire | Hulton Archive/Getty Images https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113402902

Moving backwards through the scenarios, number 3 also gives a pretty decent return, but how likely was this? First, we need to get some idea of how many ships were captured each year. Bartholomew ‘Black Bart’ Roberts was arguably the most successful pirate by number of captured ships, with over 470 ships captured during a period of four years,[16] so on average 117 each year. We’ll assume that other pirates were one tenth as productive as him, so capturing around 12 ships per year, or if you’re going on 34 ventures each year the probability of capturing a ship each venture is about 0.35. However, not all your ships will carry cargo as valuable as described in scenario 3. Let’s assume that out of the 6000[17] or so merchant vessels floating around, 800 carry cargo of the value described. The probability for scenario 3 therefore becomes 0.35 (probability of capturing a ship per venture) times 0.13 (probability of captured ship having scenario 3 cargo value), or 0.05.

Jumping to scenario 1, what would be the probability of capture? The Piracy Act of 1698 made conducting trials and executing pirates easier, leading to the execution of 600 pirates (we’ll assume that year)[18]. Likely your probability for being captured was both a function of how active you were and how successful, but we’ll ignore that here and say that 500 out of 5000 pirates each year were captured, slightly lower than the number for 1698 to account for variations in the amount of policing, a probability of capture of 0.10 that remains constant over ventures.

Given that our expected return scenarios are set up to include the whole distribution of returns, this means that our probabilities need to sum to one giving us a probability of scenario 2 of 0.85.

Assuming you’re still with me and not carried away by better things (like the rum), this means we can finally calculate our expected return of a pirate venture:

![]() [19]

[19]

And given 34 ventures per year, an annual return of £26,158. A life of crime on the high seas yielded about 3 times more than the annual merchant sailors’ pay, but not a spectacularly high sum. However, it was a life offering freedom aplenty and the hope of great treasure just one venture away.

[1] In the actual golden age of piracy someone with only one eye and one leg probably would not be captaining a ship, although the 18th century pirate Rahmah ibn Jabir al-Jalahimah did wear an eyepatch. However, pirates in this era routinely contributed shares of loot into a Common Fund which functioned as insurance and provided for any crewmembers who were badly injured.

[2] The Norse word “Vikingr” translates to raider and was therefore more a job title than necessarily a description of nationality/heritage.

[3] This name means “wife of Zheng Yi” so in the interest of feminism we’re referring to her by her birth name here.

[4] Prior to and throughout this period Barbary pirates, who operated both as pirates and privateers out of North Africa were also active. They preyed largely on ships and coastal towns in the Mediterranean, but ventured as far north as Iceland, taking near 400 prisoners in the raids known as the Turkish abductions. While the golden age of piracy is considered to have ended in the early 18th century, Barbary pirates continued their activities until the early 1800s.

[5] Pirate ships usually also counted a non-negligible number of prisoners essentially treated as slaves, so we shall avoid romanticising their organisational structure too much.

[6] Pirate euphemism for becoming a pirate.

[7] Strictly speaking, the financial risk of an asset or portfolio of assets moving more than three standard deviations from its current price, above the risk of a normal distribution.

[8] https://csphistorical.com/2016/01/24/salt-pork-ships-biscuit-and-burgoo-sea-provisions-for-common-sailors-and-pirates-part-1/

[9] https://www.royalcaribbean.com/guides/transatlantic-history-crossing-cruise#:~:text=And%20so%20began%20a%20centuries,weeks%20to%20cross%20the%20Atlantic.

[10] https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/rated-navy-ships-17th-19th-centuries

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/24-pounder_long_gun

[12] https://www.iro.umontreal.ca/~vaucher/History/Ships/Ships_Discovery/index.html

[13] Owing to data availability have used prices in the period 1753-1767 in Massachusetts US, source. However, as its doubtful that fenced goods could be sold at market price the value should probably be somewhat lower.

[14] https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1760?amount=72000

[15] During the golden age around 5000 pirates were active at any given time. If we assume that crew sizes ranged from 30-150 that gives anywhere from 33 to 166 active ships; so we’ll go midway and say that there were 80 active ships at any given time. How many ventures would each ship go on per year? Let’s say each venture lasted two weeks, and there was one week off between ventures (because our pirates are all about the work-life balance) — then each ship could go on about 34 ventures per year. 80 ships going on 34 ventures each year over a total period of 70 years gives 190,400 pirate ventures or total possible events.

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartholomew_Roberts

[17] Loosely based on information from Usher, Abbot The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 42, No. 3 (May, 1928), pp. 465-478 (14 pages) The Growth of English Shipping 1572-1922

[18] https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/bringing-pirates-justice

[19] As you’ve likely realised, deciding these returns and probabilities is a highly speculative exercise. One of my more ‘piratey’ colleagues (his description, not mine) suggested a slightly different set-up, which makes piracy appear a far more lucrative proposition:

![]()

More by this author