A sideways look at economics

Proposals for a European Super League were back in the news again last weekend after Barcelona’s club president suggested that it could start as soon as next season. For those that don’t know, the controversial proposals would see Europe’s leading football clubs enter a new midweek competition. For the league to become a reality, it will have to clear hurdles in both the European Court of Justice (which seems to be going in its favour) and the court of public opinion (which seems to be opposed). But what does the court of economic opinion have to say on the matter?

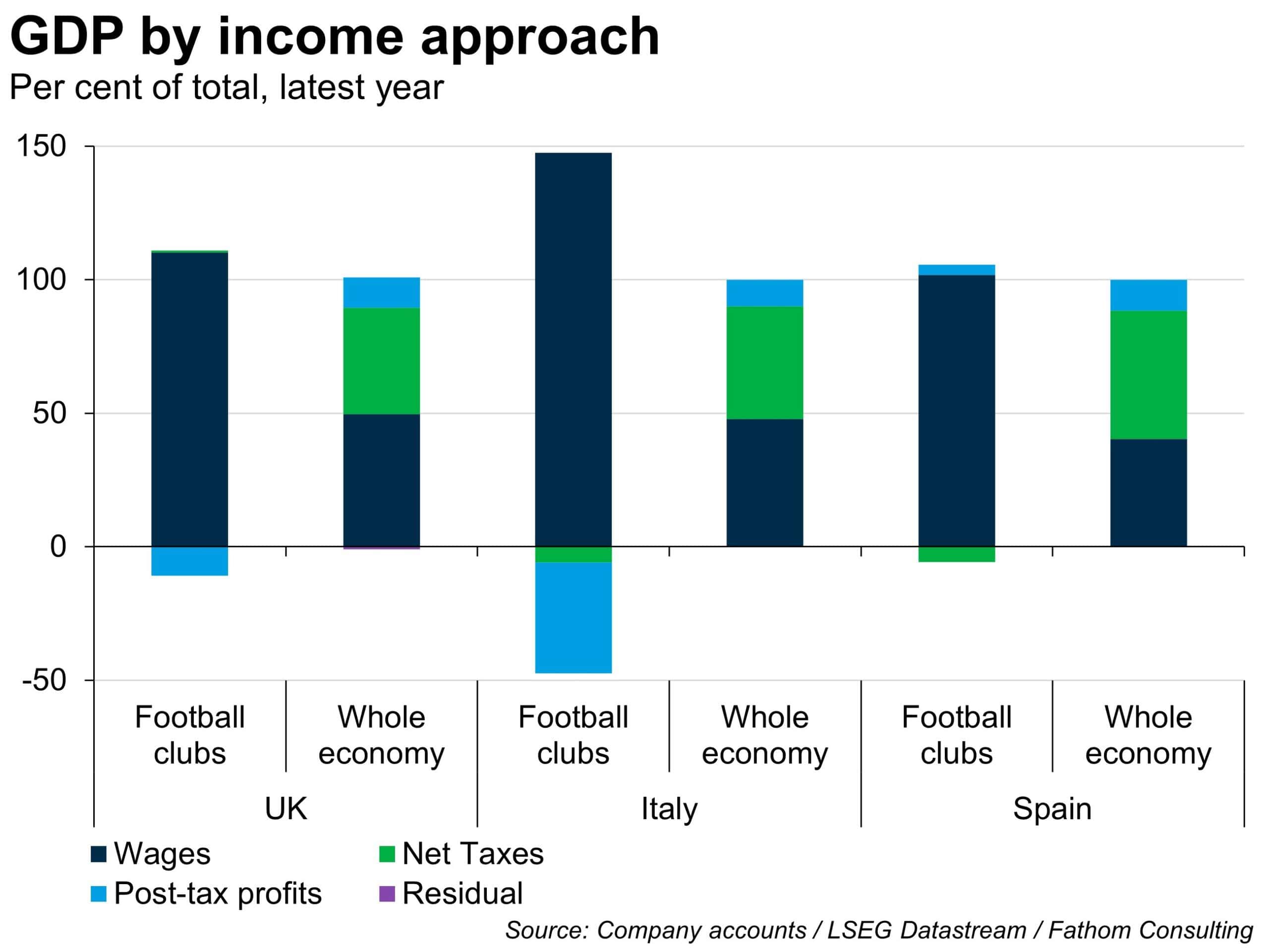

Most football clubs face financial difficulties and the motives of the organisers behind the proposed European Super League are likely to be to address these. Fathom analysis, taken from club accounts, suggests that few of the league’s founding members[1] make notable profits and many make hefty annual losses. The majority of income earned by football clubs ends up with the playing staff. This starkly contrasts with the economy-wide picture, where the share of GDP accruing to workers is in the 40–50% range and the share of domestic income represented by firms’ profits is typically around the 10% mark.

So, how might the European Super League resolve owners’ concerns about the lack of profits in football? Well, the basic problem is that wages are too high relative to the amount of revenue that clubs earn. The reason for this is that all footballers are different; each has their own skills and level of ability. Since each player is unique, a club is typically faced with few alternatives for the specific traits that one player can provide. By contrast, a player often receives interest from a number of clubs, meaning they maintain a fair degree of bargaining power. And that’s how wages are normally determined, in football and elsewhere — firms are willing to pay up to the amount of added value that an employee can provide, while employees are unwilling to work for salaries below a perceived lower threshold (what’s known as the reservation wage). The space between these two levels of remuneration is where there’s scope for bargaining.

But if the current system favours the player, how could the new system shift the balance towards owners? Relegation and promotion have always been a fundamental principle of footballing competition. And that has effectively been the case for the Champions League, Europe’s current highest level of competition — as things stand, a team playing top-flight domestic football is in theory a maximum of one year away from playing in the Champions League. Under the revised proposals, they would be a minimum of three years (which is a relatively long time in a player’s footballing career) from the Super League’s top tier. That means that a player aiming to play at the top level has fewer potential options available to them. In such a world, one might therefore posit that players might be more willing to accept a lower wage in return for their services.

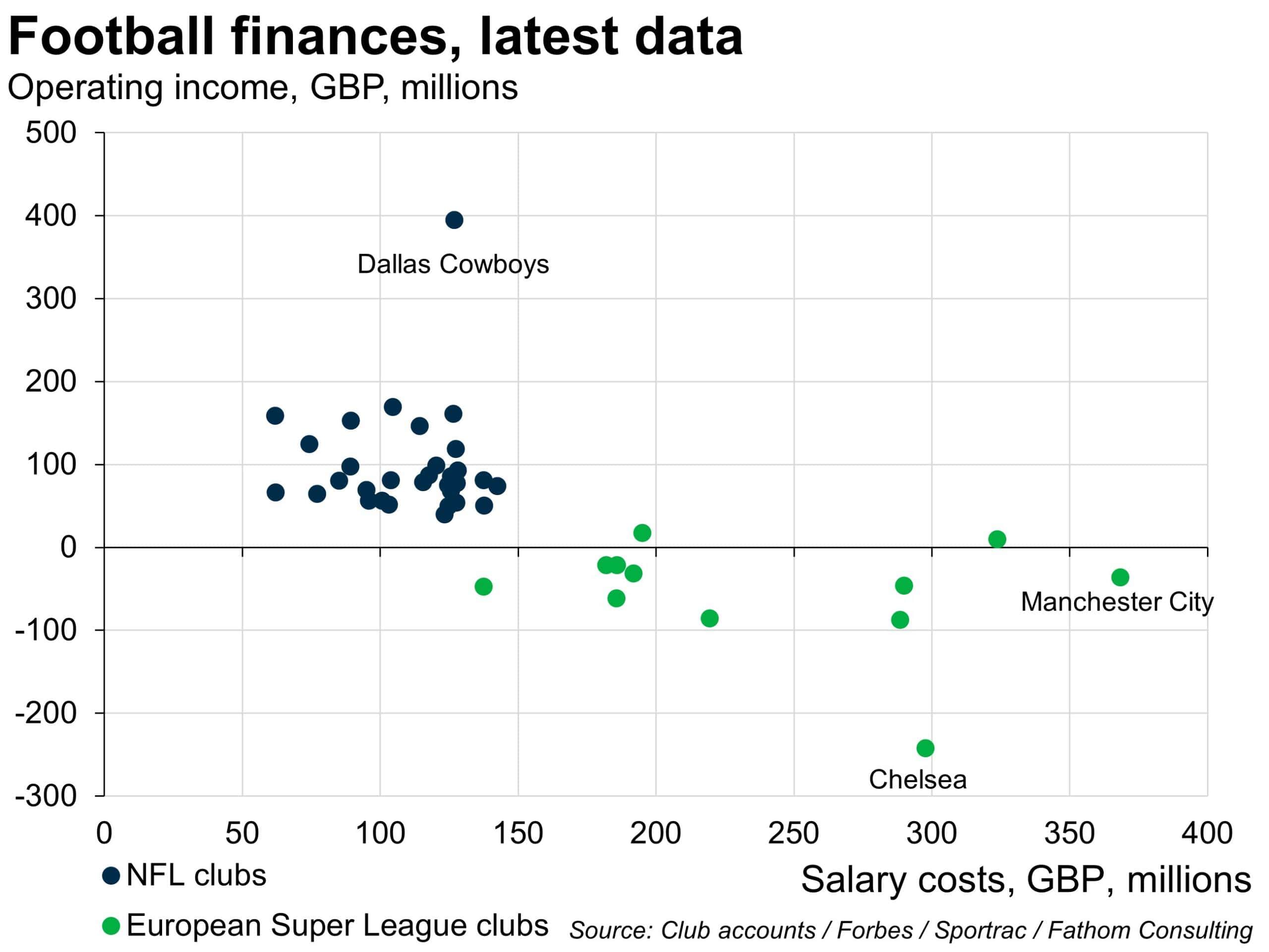

Could this work? Well, evidence from the ‘other football’ suggests that it might. The scatter chart below compares data on profits and salaries for the 36 teams of the NFL to similar data for the European Super League clubs. As you can see, the NFL teams are generally profitable and typically spend less on salaries. In part this may be due to the more closed-shop nature of the NFL, where there is no promotion or relegation for clubs, and the potential effect this could have on players’ bargaining positions. It might also be explained by the existence of the salary cap — although the league’s ability to enforce this might also be viewed as a consequence of the closed nature of the sport’s top league. Given all of this, it is easy to see why European club owners might value shifting towards a system closer to the NFL.

However, there’s more to football than money, or at least there should be. Fans appeared strongly opposed to the plans when they were first announced, particularly in the UK, and there’s little sign that this stance has changed. For many supporters, attending European Super League games would be impractical because of the expense of travelling to international midweek ties, while others object on grounds that the current set up of domestic leagues and continental cups provides better sporting entertainment. In short, while the revenue from the Super League plans could go a way towards resolving the financial problems of its clubs, it seems unlikely that those plans will become a reality for now.

[1] The founding members are: AC Milan, Arsenal, Atletico Madrid, Barcelona, Chelsea, Juventus, Inter Milan, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester Utd, Real Madrid and Tottenham Hotspur.

More by this author