A sideways look at economics

Seeing the fearless 16-year-old Luke ‘the Nuke’ Littler reach the Darts World Championship final earlier this year reminded me of my own darts performance under pressure. It wasn’t quite the same, I guess. For one thing, he wasn’t dressed as a cowboy on an inflatable horse. Littler coped extremely well under pressure, but not all of us do.

Somewhat different to the World Championship final, my performance was in an exhibition darts[1] match in front of a couple of hundred university students, all of us in fancy dress. It may have been lighthearted (myself aside, very few remember the results) but after the walkout, I was feeling the pressure. I clambered onto the stage and had three practice darts to get my eye in. They all missed the board. I am no Luke Littler but I can usually hit the board!

In an effort to excuse this embarrassing showing, I have looked into how pressure impacts performance. Darts is perfect for this since it’s almost the same physical action for every dart you throw, and the opposing player cannot make your shot more difficult. (That is, apart from one instance in 2018 where players accused each other of leaving fragrant smells behind.[2])

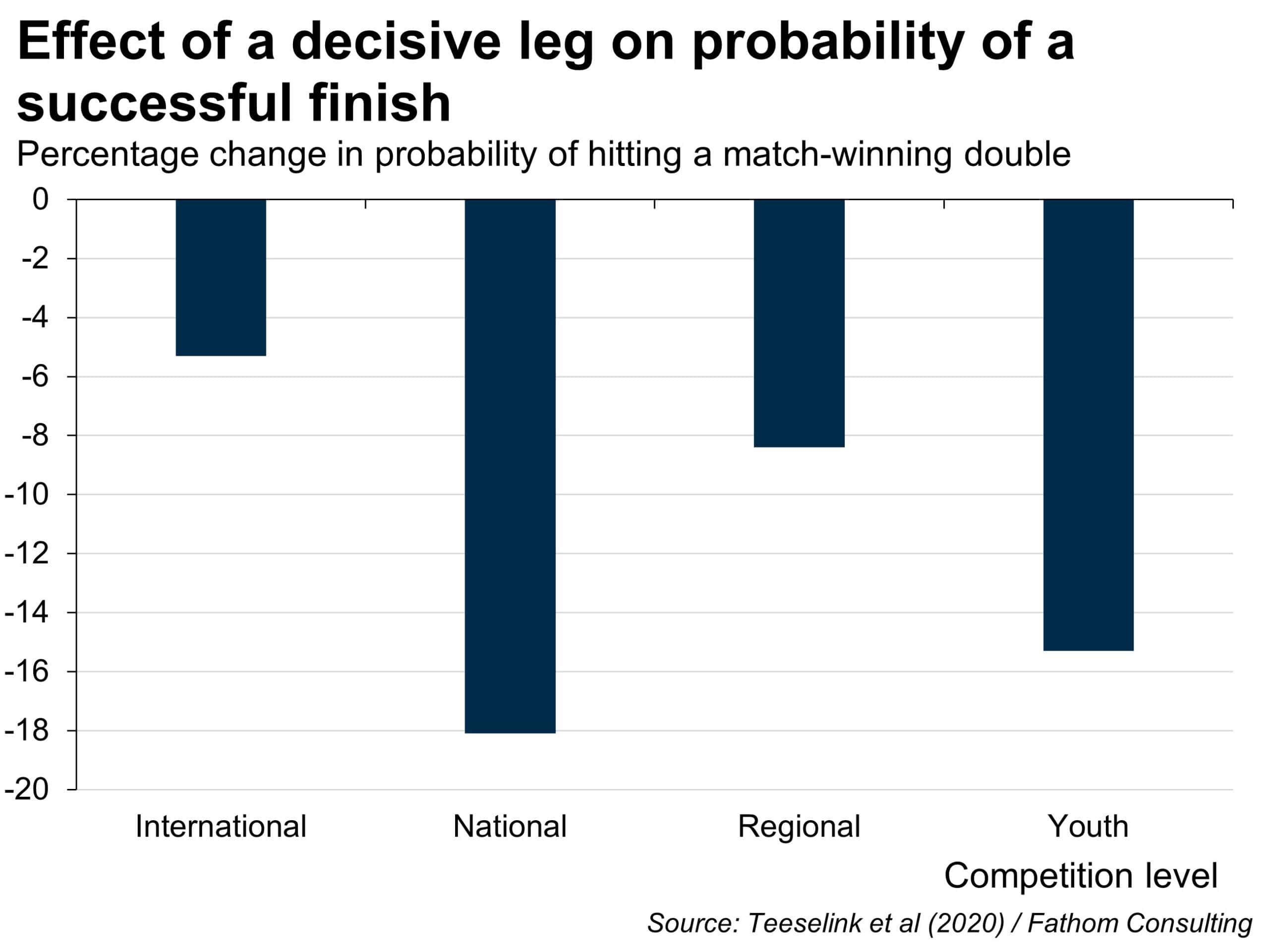

Using data from thousands of legs of darts at different levels of competition, Teeselink et al (2020)[3] found that when a player was under high pressure (due to throwing in a decisive leg) the probability that they would successfully win the leg was reduced. This finding held for all levels of competition, but to differing extents.

In addition, they found:

- The effect of a decisive leg on a youth player’s finishing probability was a reduction of 15.3%

- The impact was largest on national-level players (18%) — possibly because they have a higher finishing probability when not under pressure, and may be more nervous due to the higher rewards at national level

- For international-level players, the effect was least detrimental, reducing the finishing probability by 5% — they are seemingly less phased by pressure despite huge stakes, a trait that would’ve helped these players reach this level

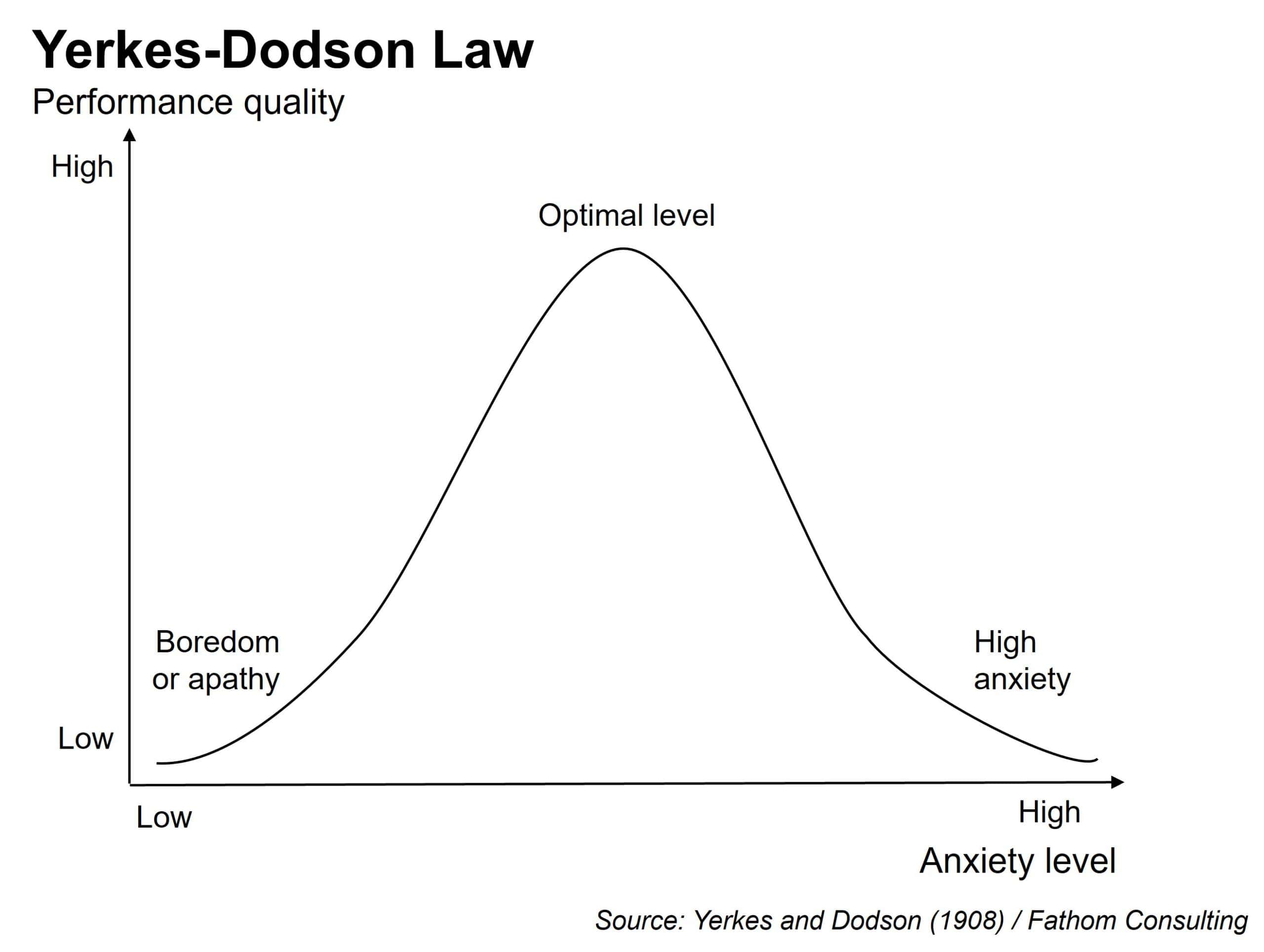

Worse performance under pressure can be explained by the Yerkes-Dodson law, which originally found that both under- and over-stimulation lead to slower habit-formation and learning.[4] This has since been interpreted as an argument that both boredom and high anxiety will lead to poor productivity. Peak performance is found at an optimal level of pressure creating this bell-shaped curve. In reality, performance is likely to drop very steeply after hitting a point of anxiety which can’t be dealt with. It’s easy to see how this can be applied in a sporting context (yes — I consider darts to be a sport).

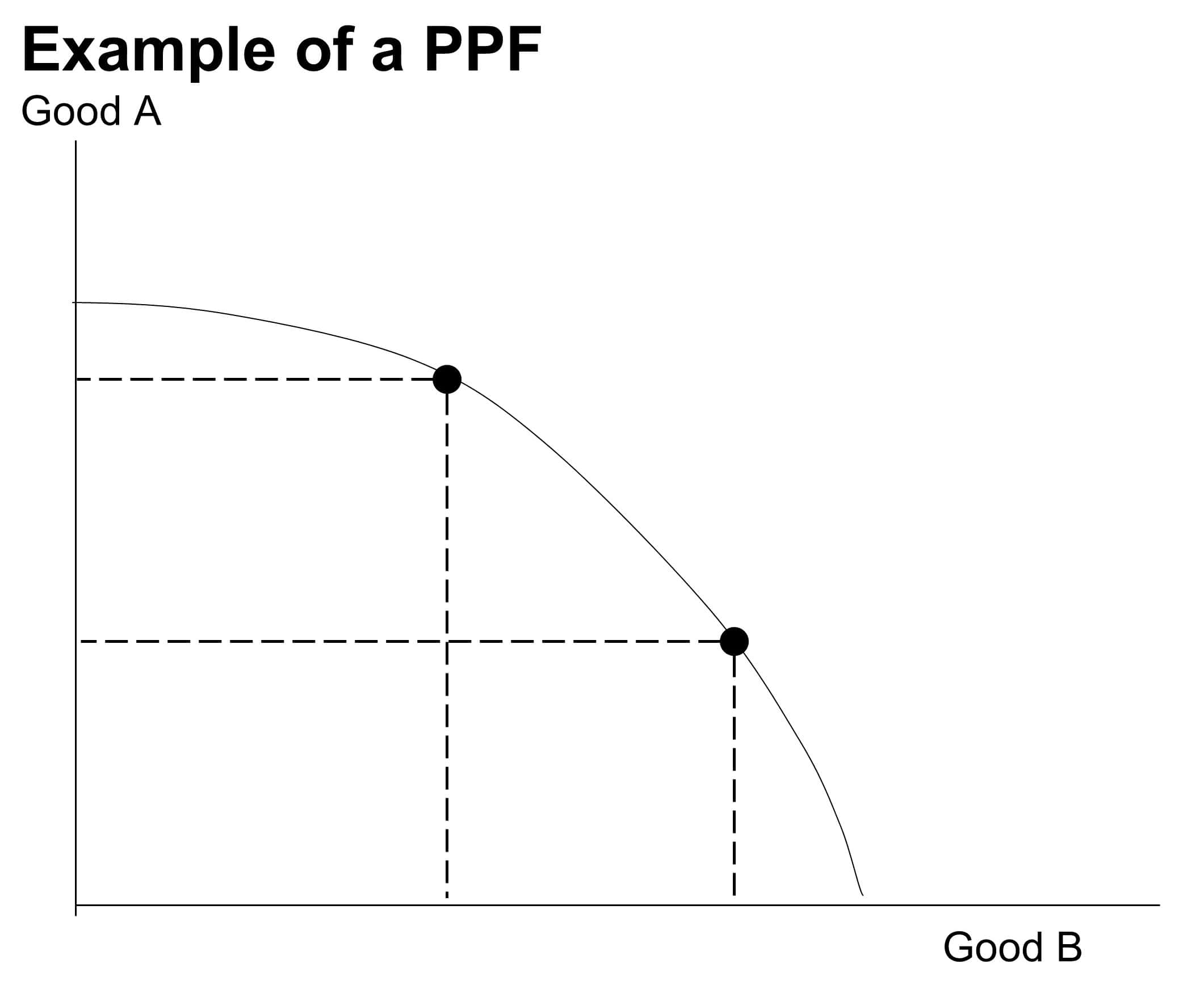

And it’s not just athletes that are affected by high-pressure situations. In the workplace, productivity can be greatly affected by the pressure we face — when working towards an important deadline, for example. In their chapter on productivity, economics textbooks often introduce you to the production possibility frontier (PPF), which shows all possible output combinations that an economy, firm or worker can produce given their resources. Firms and workers are assumed to be efficient and operate on this frontier, at their maximum capacity, and therefore pressure could not improve productivity due to the limit of the PPF.

But do workers and therefore firms always operate at maximum capacity? Even if they wanted to, it is unlikely that this could be done in perpetuity without suffering from ‘burnout’. In reality, most firms may operate inside their PPF in steady state. That is until pressure arises during a period of intense work (e.g., a looming deadline) which pushes workers onto their PPF, working at maximum capacity. This may not be sustainable in the longer term as workers tire and the cumulative effect of stress becomes overwhelming so productivity falls. At this point, reducing pressure may provide efficiency gains, as implied by the Yerkes-Dodson law.

Alternatively, it could be said that pressure levels cause shifts in the PPF in the short term. Cycles of intense work come around, encouraging workers to work intensely. This causes an outward shift in the PPF, increasing the amount of possible output. On the other hand, if stress exceeds a manageable level in the short term, the PPF could shift inward, reducing productivity. In this context, the production possibility frontier would represent the long-term sustainable level of output.

Sustained shifts in the long term would have to be achieved by investment. For an individual worker this could be through training, where the worker improves their skills (maybe learns new techniques) and then becomes more productive. Their PPF curve would shift outward as at every given level of inputs and pressure, the worker can produce more. A similar result could happen with specialisation (workers can produce more at each level if they focus on one task, as they will become more skilful over time). A firm increasing capital per worker, e.g., providing greater access to (or improving) technology, will also shift the curve outward as it can help workers produce more for a given level of resources.

Taking this argument back to darts, in the short term some pressure may incentivise a darts player to increase focus as much as they can, and so operate on their PPF. When already at this level, the increasing pressure may begin to have the detrimental effect that Teeselink et al found. For long-term improvements in performance, training is needed for athletes, so technique becomes almost muscle memory. As the skill level increases with practice, then at every level of pressure, performance can be higher — mirroring how workers’ productivity too can be improved[5] Productive potential cannot automatically be boosted just because there is pressure. It needs to be preceded by investment and it has long payoff horizon.

For example, after devoting time into practice we can see unbelievable performance, even under pressure. For a great example, I recommend watching Michael Van Gerwen and Michael Smith both aim for a 9-dart leg[6] on the biggest stage during the 2023 Darts World Championship final.

So, I’ll get back on the horse and invest some time into practising. And if you see Ed ‘Wild’ West back on the darts stage, he will hit the board… maybe even multiple times!

[1] Here is a quick explanation for those that do not know the sport of darts. Players throw darts at a round board that is divided into numbered sections, aiming to score points, which are taken away from 501, by hitting larger numbers. The ‘leg’, or round, is won by ending on exactly 0, hitting the double segment of the board.

[2] https://news.sky.com/story/darts-players-let-rip-as-they-accuse-each-other-of-farting-during-match-11557078

[3] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167268119303439

[4] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cne.920180503

[5] Higher capital per worker will increase their productivity in the long-run but new darts have a limited impact on the performance. At least that is what my spending has showed me.

[6] A 9-dart leg is the perfect leg of darts using the lowest amount of darts possible to finish on a double at exactly 0 from 501. Its estimated to happen in 1 in 5,000 legs for a pro.

More from Thank Fathom It’s Friday