A sideways look at economics

I often wonder why people vote in the way they do. Are they voting in what they perceive to be their own best interests, or in the wider interests of society as a whole? Indeed, why do we vote at all? Is democracy the best form of government?

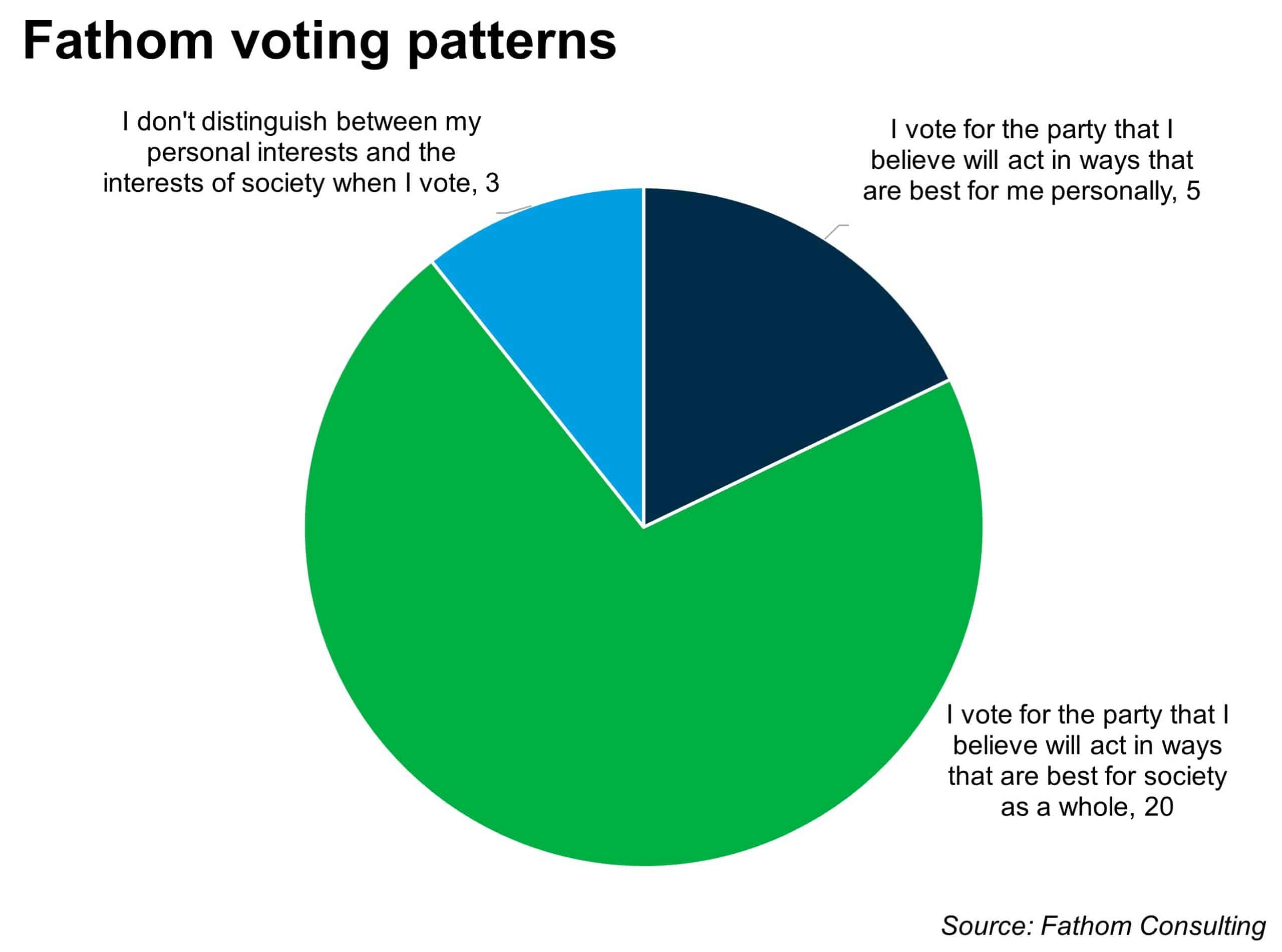

On the question of why we vote in the way we do, an anonymous straw poll of Fathom employees gave the results below.

The majority vote for the party that they believe will act in ways that are best for society. And, in a separate question, nearly two-thirds feel no attachment to either major party. There is no right and wrong that I’m aware of here and, of course, Fathom is not representative of the population as a whole. Imagine it were for a moment: how would that change the way politicians shaped their message? Most Fathom employees do not feel a strong sense of party loyalty, and most vote in the interests of society as a whole.[1]

Speaking for myself, I don’t think I can point to a single instance when I’ve voted other than in what I perceive to be the interests of society as a whole, even when they run directly counter to my own interests. My own interests barely register. I am not saying this is the ‘right’ way to vote: I wouldn’t know. But it’s the way I vote. I personally feel that messages aimed at persuading me I’ll be £x better off under a government of such and such a hue are actively off-putting. Irrelevant at best; at worst, conveying the sense that the party sending that message thinks I can be bribed to support it. Messages that emphasise the bigger picture, what we want for the society we live in, are much more likely to gain traction with me and, it seems, with most of Fathom. Perhaps that’s just us, though. How about you, reader?

2024 is the year of elections in many countries, which is what has spurred me to think about democracy. Panning out from the way we vote to why we vote at all, Churchill declared democracy to be the worst form of government except for all the others. Democracy has its shortcomings but I think a stronger case than that can be made for its advantages: so here goes, borrowing shamelessly and without attribution from Mill, Hume, Bentham, Acton, Lindsay, Rawls, Keynes, Arendt, Barro and many others.

First, let me explain what I think is the best form democracy can take. I do not believe in plebiscite democracy. The fact that the majority of voters supports a particular position usually has no bearing on whether it is sensible or otherwise, and a majority can become a mob in some circumstances, with potentially terrible consequences if that mob directly controls the levers of power. I support representative democracy.

I am not aware of any election, national or local, that has been swung by one vote. If there were such a case, there would certainly be recounts until a clearer result emerged. Consequently, my vote (or yours) is irrelevant, considered individually. For democracy to work, it is essential that most people should vote in spite of that logic. Because of this, I would make voting compulsory, with the proviso that there should be a ‘none of the above’ option available on every ballot paper.

I do not believe that our elected representatives are wiser or more immune to factors that can sway the mob than the rest of us, on the whole. And, because of their greater influence, they are more likely to be subject to attempted bribery or blackmail than we are. So, if we’re not careful, the decisions they make are likely to be as bad or worse than the decisions that the plebiscite would make on the same issues. That is why a system of representative democracy needs checks and balances, as well as severe, exemplary penalties for giving or accepting bribes or for blackmail of any kind. Such checks and balances are feasible with representative democracy, but much less so with the plebiscite: ‘The people have spoken! Make it so!’

It should be very hard for our elected representatives to effect big changes to anything: hard, but not impossible. Making it hard is achieved by having an independent judiciary; an independent civil service; independent media; and an unelected second house. If the second house were also elected, it would be subject to the same pressures as the House of Commons and would be ineffective as a balance to the power of the Commons as a result. In my ideal world, the second house would be drawn from the electoral register at random like juries (with the same kind of selection criteria). If your name were drawn, you would be legally obliged to serve for a fixed term of perhaps three years, with six months’ lead time, and one third of the house turning over each year. Your employer would be compensated generously, as you would, tax-free, during your period in office. Your constitutional duty would be to vote with your conscience at all times. As now, the second house would be able to amend and to delay legislation (though not forever), but not to initiate it.

I believe that power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Therefore, no individual or party should ever be granted absolute power, and such power as they do enjoy should be temporary. The great advantage of democracy is that it ensures a peaceful and regular transfer of power, between individuals and between parties. It matters far less which party is in power than that whoever it is should be regularly removed from office; and the same applies to individuals. Therefore, the system of democracy that I support is one that ensures of the incumbent from office.

This points me towards the much-maligned first-past-the-post voting system that we have in the UK. Proportional representation has the advantage of reflecting the spread of voters’ preferences in the elected chamber more accurately. But it has the huge disadvantage that the same people and the same parties (albeit in slightly different coalitions) , with all the attendant problems of corruption.

That is what I believe democracy should look like. The main advantage of such a system in my opinion is that it is the best means we have of protecting the freedom for people to live more or less as they choose (within the law, where the aim of the law should be principally to prevent one person or group from infringing too much on the autonomy of any individual). Maximising the space within which people can live freely: that is the central principle of democracy as opposed to authoritarianism of whatever kind. It’s not so much the decisions that the democratic government makes that matter; it’s more the preservation and extension of the space in which government doesn’t matter at all. No matter how it starts, a government that is permanently in office will become corrupt, will gradually erode the checks and balances that limit its power, and will in the end, through fear of being overthrown, attempt to control all aspects of our lives. A democracy that regularly ditches the incumbent is the best protection we have against that eventuality.

I support a constitutionally powerless and unelected titular head of state. People feel very strongly about national identity and it is important that those feelings should not be attached to individuals who have control over the levers of power. A constitutional monarchy is anachronistic in many ways, but it has the tremendous advantage that national pride is separated from the messy and often boring, technical business of making policy.

Finally, preserving and extending the area within which people can live freely is also the best way to encourage creativity, innovation and growth. Autocracies and totalitarian societies are sometimes very good at catching up with the global technological frontier and scaling up those technological advances. But they are typically very poor at advancing the technological frontier: it is hard to be creative within predefined boundaries, and harder still to want to innovate at all on behalf of a totalitarian government. Democracy is not just good in its own right: it is also good for growth, which is what makes it strong in the long term.

One problem that arises from democracy is that, by demonstrating a means of government that preserves both individual freedom and growth, it creates a threat to autocracies. People, I believe, would generally prefer to live with a high degree of autonomy and, if they are deprived of that but can see current examples of thriving economies where autonomy is preserved, they will push for that option when they can. So autocracies continually try to undermine democracies by word and deed, usually while closely controlling the flow of information to their own populations. As a result, while democracies tend not to go to war with each other (as a general rule, not always observed), they do frequently go to war with autocracies and/or totalitarian governments (who also frequently go to war with each other). For as long as the world has lots of autocracies still in it, conflict between them and democracies is more or less inevitable.

Representative democracy, first-past-the-post, within a constitutional monarchy where the unelected head of state has no constitutional power: that’s the best option in my opinion. Also, it’s the one we’ve got. There has been a good deal of discussion, this year particularly, about whether other options might be preferable: I am a small-c conservative in this respect. Any kind of democracy is better than any kind of autocracy, but within the class of democracies, the version we have in the UK is the best in my opinion, for all its faults. Judging by the reaction of my friends and colleagues to this position, I expect it to be controversial. Let’s hear it!

[1] Some will argue that your own interests are best served by ensuring that society as a whole is thriving and, according to your lights, fair. Kant argued that you cannot be construed as acting morally if what you do serves your own interests, even if it also serves the interests of others or of society as a whole. Pure altruism, for him, is where your own interests are irrelevant. You might still argue with Kant that it is in the interests of your eternal soul (for those who believe in such a thing) to act morally, so even the purest form of altruism is still impure in that respect. These arguments can go on endlessly. I prefer to stick with how language is normally used: in your own interests, or those of society as a whole?

More by this author