A sideways look at economics

It’s always fun to mock politicians. So, when I saw UK Chancellor Jeremy Hunt announce his ambitions for the UK to possess a one-trillion-dollar homegrown company within ten years, I thought another opportunity was coming my way. But then I started imagining whether it was actually possible…

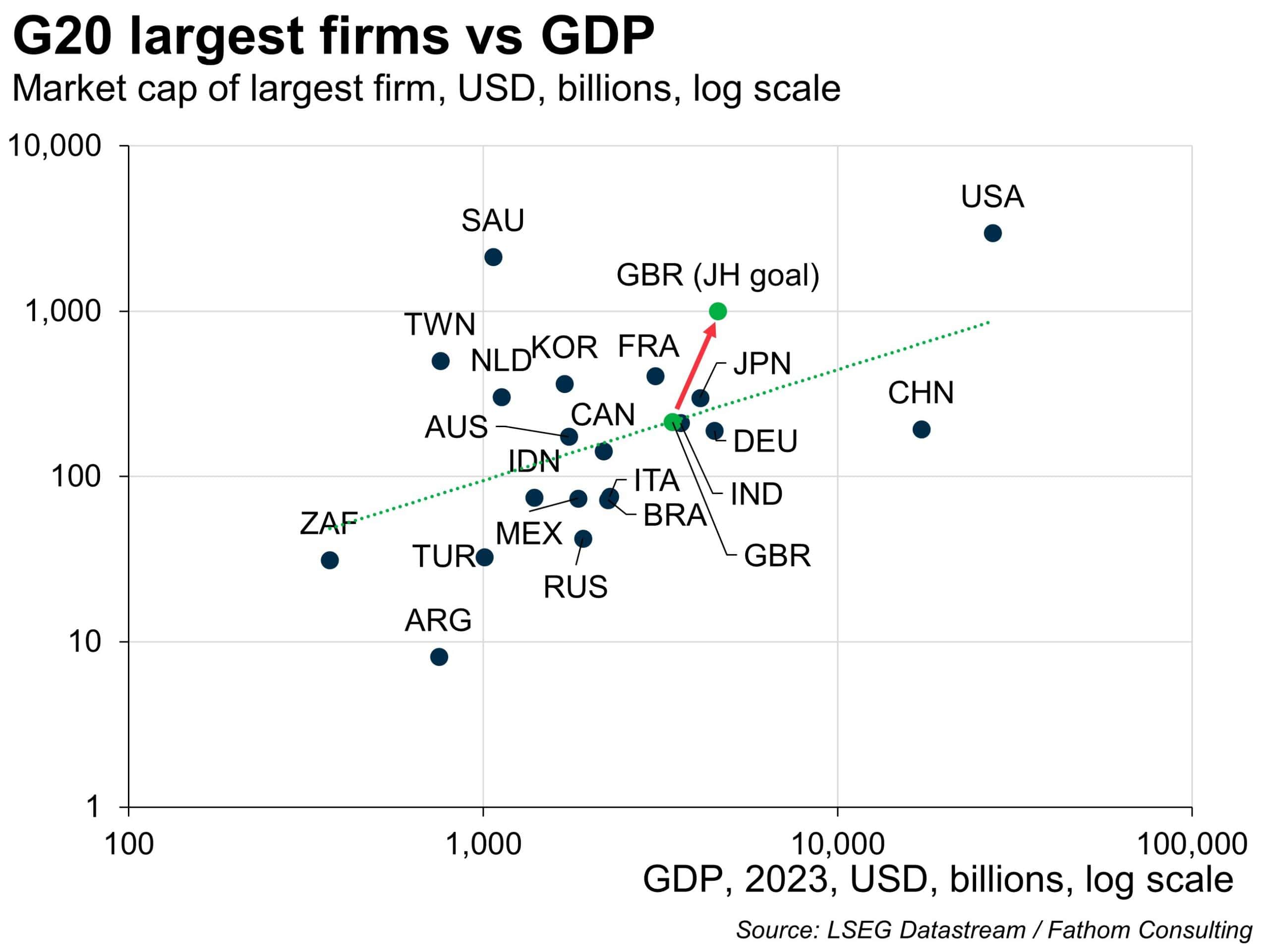

Unsurprisingly, in turns out that there’s a positive correlation between the size of a country’s economy and the market cap of its largest publicly listed firm. The chart below shows this relationship for the G20 economies, plus Taiwan and the Netherlands (more on those two later). The data for this are taken from the Datastream Market indices for these countries. Some nations (e.g., Saudi Arabia) stand significantly above that best-fit line while others (e.g., China) stand way below it. The UK’s most valuable firm (Shell) stands bang on that line. So ‘Blighty’ is neither underperforming nor outperforming in this regard. But, as our last two TFiFs have argued, it’s good to be good. In other words, we should aim a little bit higher!

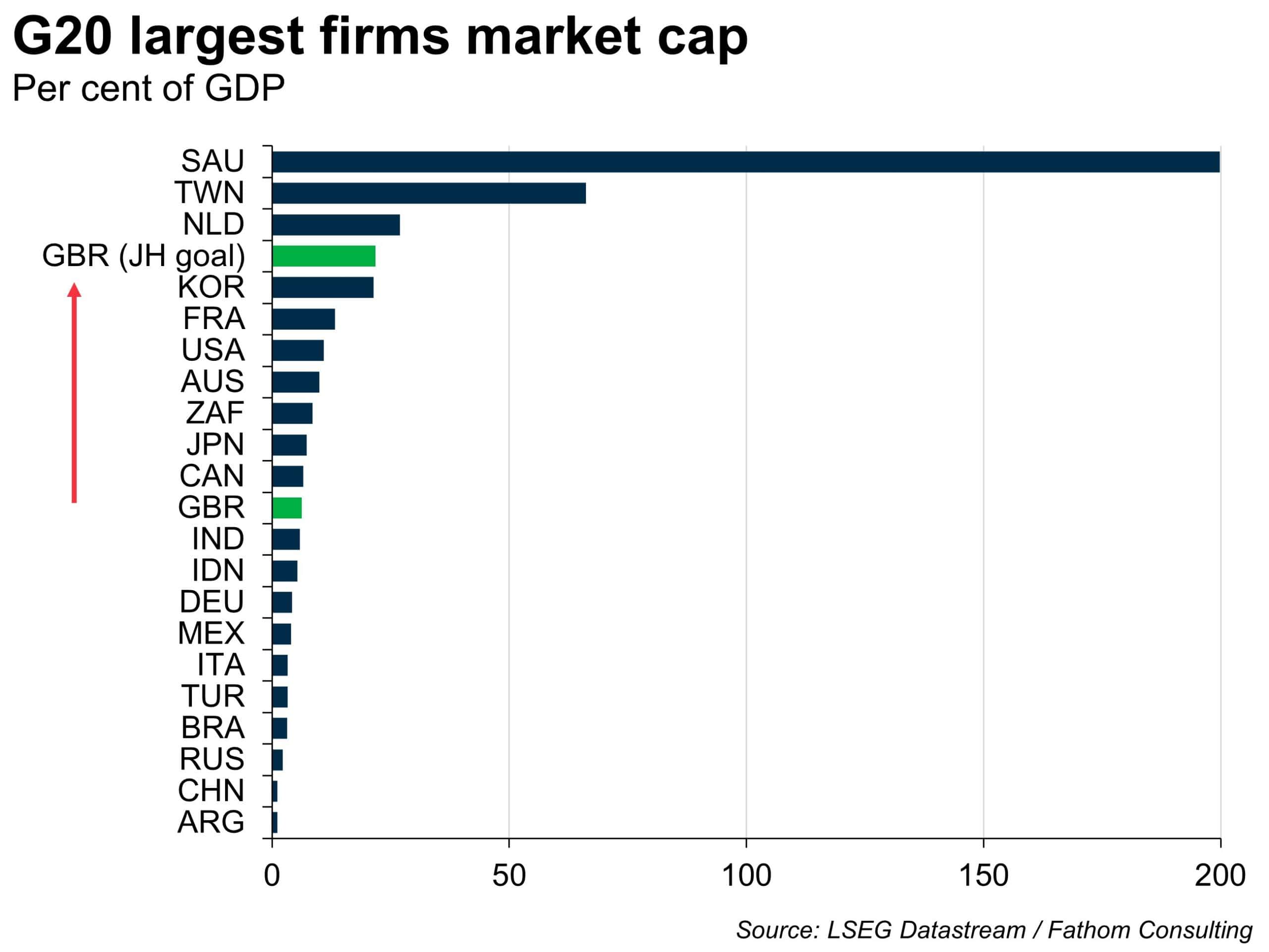

One-trillion dollars is of course almost five times as large as Shell’s current market cap. Creating a company that sizable will not be easy, but perhaps not impossible. The UK’s economy might be expected to grow by around 3–4% annually on a nominal basis over the next ten years. Taking the midpoint of that range, a trillion-dollar company’s market cap would be equivalent to around 20% of UK GDP. Crazy, right?

Actually, no! Looking at the chart below, that would place the UK just below Korea, Taiwan and the Netherlands. Saudi Arabia is obviously an outlier here due to Aramco’s extreme natural resource wealth. However, the results for the others are all due to ‘innovative tech’ manufacturing firms (Samsung, TSMC and ASML respectively). Could the UK replicate that success? On the one hand, perhaps, we are relatively less good at manufacturing than we used to be, but on the other hand we still score highly on survey-based measures of innovation.

There are of course a number of barriers that stand in the way of Mr Hunt’s ambition. The first is obviously the lure of the US. Startups, such as Stripe (founded by Irish entrepeneurs) and Tesla, serve as recent examples of founders looking to start their businesses in the world’s financial centre. That said, if you are looking for funding opportunities outside of the states, you will not find many places better than the UK.

A second factor hampering the chancellor’s ambition is the threat of overseas takeovers. Indeed, in recent years UK chipmakers ARM and Nexperia have been sold off to overseas investors, as has AI start-up Deepmind. This is not necessarily a bad thing for the UK economy, but it does make the dream of a trillion-dollar company more difficult.

For the sake of keeping this blog short, the final obstacle that I shall mention is market size. The US economy is about eight times as large as the UK’s. The EU is a similar size. Firms can of course trade internationally, but it is much more difficult to grow out of a smaller market.

There is of course still a discussion to be had about whether a company of this size would be a good thing for the UK economy. My view would be yes, provided it could be incentivised to continue innovating intensively. Large companies, as we know, do not always do this… Putting that debate aside for now (we could write an essay on the topic), it does seem as if there’s a chance that the aspirations of a trillion-dollar company aren’t too far fetched. I’m not saying it is likely, but certainly the idea should not be invalidated when discussed in and around the House of Commons. Because, as we all know, you never get anywhere without a bit of ambition…