A sideways look at economics

I reached an important chronological milestone this year. In early March I turned 50. A few days before this important event I was due to speak at a conference in Warrington. It was to be my first appearance in a suit since the pandemic hit. I was able to find assorted jackets and trousers hanging up in the office, and yet more in a wardrobe at home. But I struggled to put together a matching set. Having moved house last year, I concluded that the missing parts were either in an unopened box somewhere, or irretrievably lost. So I resolved to buy a new one. Much to my disappointment, I discovered that I had gone up a size. That, together with the passing of another decade, and perhaps one or two kindly suggestions from family members, convinced me to do something about it.

I spoke with a friend, younger than me, who had recently shed a good few kilos with the help of an app called MyFitnessPal. He suggested I take a look, which I did. It seemed very thorough, and very scientific. It certainly worked for him. I decided to give it a go.

You start by entering a few basic details – age , sex, current weight, desired weight, and so on. It then asks about your lifestyle. These were my options:

- Sedentary. Spend most of the day sitting (e.g., bank teller, desk job)

- Lightly active. Spend a good part of the day on your feet (e.g., teacher, salesperson)

- Active. Spend a good part of the day doing some physical activity (e.g., food server, postal carrier)

- Very active. Spend most of the day doing heavy physical activity (e.g., bike messenger, carpenter)

Well, if we’re going to define our lifestyle with regard only to the nature of our employment, then I’m clearly in the sedentary category. So that’s the box I ticked. The app went away, thought for an imperceptibly short period of time, and told me I needed to stick to 1,648 calories per day, and that would enable me to lose weight at the recommended rate of half a kilo each week. I balked slightly: it seemed a small number. But I quickly came round to the idea. The app makes it very easy to monitor the nutritional value of more or less anything you eat, allowing you to scan barcodes on products you buy from the supermarket, or enter the ingredients of a meal you’ve prepared yourself.

I began, dutifully, to log my meals – broken down into breakfast, lunch and dinner, with everything else logged under the troublesome heading ‘snacks’. Shortly after lunch, as I refreshed the app, I got a pleasant surprise. The arithmetic had shifted dramatically in my favour. It turns out MyFitnessPal had miscalculated my calorific needs because it had made no allowance whatsoever for exercise. It assumed that, as a sedentary economist, I literally sat in my chair all day long. When I commute to the office, as I did last week, I often walk close to eight miles a day, particularly if I go out to buy lunch, and perhaps head to the shops on the way home. After conferring with my Fitbit watch, MyFitnessPal had added more than 1,000 calories to my budget for that day.

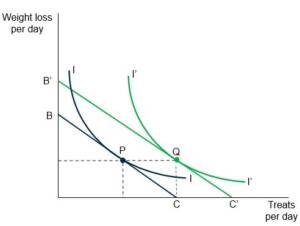

What to do? Do I stick to the plan, resist temptation, and lose weight even faster? Or do I spend the additional calories on what one might loosely term ‘treats’? Of course, this is a standard consumer choice problem, of the kind faced by students of A-level economics (albeit under a slightly different guise). I plan my optimal combination of weight loss and treats given what I believe to be my available budget, and then joy of joys, learn I actually have more to spend. Diagramatically, I start at a point like ‘P’, where my indifference curve (IC), which describes combinations of weight loss and treats that I find equally desirable, just touches my budget constraint (BC), which describes combinations of weight loss and treats that are open to me – at least, according to the app. But because the app had made a mistake, assuming I was doing no exercise at all when I fact I was doing quite a bit, in truth, my budget constraint was B’C’.

How did I spend this additional income? Well, from the way I have set up the indifference curve map in my diagram, you can see that I chose to spend all my hard-won calorific surplus on treats (on this occasion of the liquid kind, since you ask) rather than weight loss, moving from point P to point Q. I was on a higher indifference curve, I’I’, which means I was having more ‘fun’! Treats, in this set up, are most definitely a ‘normal good’ – one demands more of them as one becomes better off.

After conferring with friends, I discovered that this is quite a common response on first discovering that one has more calories to play with. But as the days have passed my preferences have shifted somewhat. Now I tend to spend around half of any windfall gains, choosing to bank the rest. Only time will tell if I am able to reach my target weight in the time promised to me by MyFitnessPal. But so far, so good.

More from this author:

The art of economic forecasting